Home on seven days boiler cleaning leave from Royal Navy Destroyer Westcott, based at Gladstone Docks, Liverpool, the convoy base, 1940.

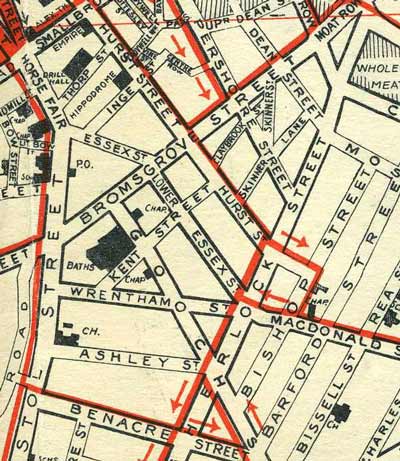

After a couple of days at home, one Tuesday evening at about 7.30 I decided to visit an old school friend. I was informed by his mother that he was visiting his sister who lived in Bishop Street. A few minutes after arriving and meeting my friend Jim Farrell and sister Sally and Annie as well as some friends, the Air Raid siren sounded. Jim and I opened the back door, looked into the moonlit night and saw a solitary plane. No guns were being fired.

After a couple of days at home, one Tuesday evening at about 7.30 I decided to visit an old school friend. I was informed by his mother that he was visiting his sister who lived in Bishop Street. A few minutes after arriving and meeting my friend Jim Farrell and sister Sally and Annie as well as some friends, the Air Raid siren sounded. Jim and I opened the back door, looked into the moonlit night and saw a solitary plane. No guns were being fired.

Then Annie called us to come in and go down the cellar, “It’s OK, it’s been reinforced with girders so we will be alright”, she said. All I could think of was my mother at home with my gran and brother, I wanted to make sure they were alright, but there was no time.

After being down the cellar about five minutes or less I found myself buried in bricks and rubble up to my chest. I do not remember hearing a bang. After a few minutes I eventually freed my arms and as I looked up I could see the sky and it seemed I was at the bottom of a tunnel. The more I tried to pull myself out the more I was covered in old plaster and broken wooden lathes. My body was rigid and I was not able to move. I remember hearing Sally cry out "Please help me", I called back, "I can't, I'm stuck and can't move".

Nothing more until I woke up on Wednesday afternoon in the Queens Hospital, Bath Row, the centre of Birmingham. When I woke there was a person at the side of my bed who said he was a police detective, he gave me a cigarette and asked me a number of questions, then left leaving me the almost full packet of Players cigarettes.

After two days in Queens and being visited by one of my brothers, who told me he had seen my name on the casualty list outside Digbeth Police Station. I was relieved as my mother knew I was alright, and I knew they were alright. I was also concerned about my Burberry raincoat as it contained my Pay Book, Identity Card, and also six one pound notes inside. (Gone but not forgotten). I was then taken by an American Red Cross ambulance to Rubery Hospital for the service wounded. I was treated for bruises and swollen limbs. After seven days I was allowed home. My mother had cleaned my uniform as I refused to wear the hospital uniform of white shirt, red tie, and light blue suit, worn by wounded service men.

Catching the tram to Brum I stopped at Bristol Street and walked down Wrentham Street towards my home in Barford Street, I called at the public house in Wrentham Street, I decided I would like a drink. Buying half a pint of mild I looked at the side of me and a man was holding a collection tin.

"What's that for?" I asked him.

"It's for the widow of the Home Guard who died of gas poisoning being lowered down that hole in Bishop Street", he said.

"I'd been told it was a land mine and took a row of houses. Was the person rescued?" I asked.

"Yes”, he replied, “eventually, it's a sailor, I do hope he's alright?

When I mentioned the sailor was me he nearly fainted. "Do you realise you are the only one out of twenty to survive?" he said.

The lad who was also rescued lost a leg under the cellar girder and died under the operating table of shock from losing his remaining leg.

© Ernie Humphreys 2003 (see also below)