Two Birmingham businessmen

pause for a moment on a sunny Berlin street to have

their photograph taken. It is 1932, the last summer

before Germany starts to change for ever.

My father is on the

right. The identity of his colleague is unknown. We

are on the Charlottenstrasse, a smart area of central

Berlin. Exactly why we are here I cannot tell you. But

what is certain is that we are engaged in some sort

of business on behalf of the company we work for, ICI

at its Kynoch Works on the outskirts of Birmingham.

It is a fairly ordinary scene

showing a moment of eighty years ago frozen in time

and history. But take a moment to look at some of the

detail and think about what it represents.

Ignore my father's sartorial

elegance, if you will. Look instead at the car, a Riley

Monaco of late 1930 or early 1931 vintage, with its Birmingham

registration number-plate and standing at the kerb, a

long way from home. Think of the journey it has made,

before the first autobahn has been built and before the

advent of car ferries, being hoisted by crane off a ship

at Hamburg or The Hook of Holland before travelling hundreds

of miles east to the capital. It appears to have survived

the outward journey in good order. But another long slog

faces it before it sees Birmingham's streets again.

And

look at the other vehicles and especially the taxi, waiting

on the far side of the street, in the Kronenstrasse to

the right. The cabbie is looking across at us, his expression

one of idle curiosity as he awaits his next fare; or is

it one of unfriendly suspicion as he looks at this group

of foreigners and their unfamiliar vehicle? And who knows,

perhaps only fifteen or so years previously he and my father,

as mere boys filled with fear and hatred, had peered out

at one another from each side of an expanse of tangled

barbed wire and French mud.

And

look at the other vehicles and especially the taxi, waiting

on the far side of the street, in the Kronenstrasse to

the right. The cabbie is looking across at us, his expression

one of idle curiosity as he awaits his next fare; or is

it one of unfriendly suspicion as he looks at this group

of foreigners and their unfamiliar vehicle? And who knows,

perhaps only fifteen or so years previously he and my father,

as mere boys filled with fear and hatred, had peered out

at one another from each side of an expanse of tangled

barbed wire and French mud.

Behind

the two men, on the left in the distance and beyond some

trees, one can just see an imposing and massive building,

so typical of the city and its 19th century grandeur.

Behind

the two men, on the left in the distance and beyond some

trees, one can just see an imposing and massive building,

so typical of the city and its 19th century grandeur.  It

is the Concert Hall (Konzerthaus am Gendarmenmarkt). Between it and us, hidden around the corner to the right,

is Berlin Cathedral (Berliner Dom). Walk further

up the street, past the Concert Hall, and one finds oneself

in Unter den Linden, an elegant, tree-lined thoroughfare,

the German equivalent to the Champs-Elysées (right). Over the ensuing hour or two

my father strolls around that part the city with his colleague, taking in the sights and recording a few of them.

It

is the Concert Hall (Konzerthaus am Gendarmenmarkt). Between it and us, hidden around the corner to the right,

is Berlin Cathedral (Berliner Dom). Walk further

up the street, past the Concert Hall, and one finds oneself

in Unter den Linden, an elegant, tree-lined thoroughfare,

the German equivalent to the Champs-Elysées (right). Over the ensuing hour or two

my father strolls around that part the city with his colleague, taking in the sights and recording a few of them.

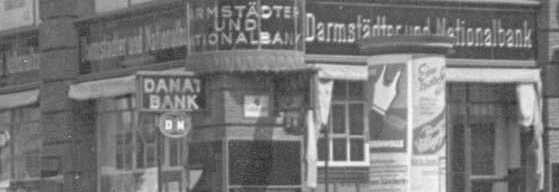

Now look at the building

on the corner. It is a large branch of the Danat Bank

(in full, die Darmstädter und Nationalbank),

the second largest bank in Germany - the equivalent of

a Lloyds or Barclays. But nobody seems to be near it.

The reason is quite simple: it has closed. The previous

year catastrophe struck. The bank fell victim to the worldwide

slump and the resulting impact on the German financial

institutions. And it has failed.  With

that failure and the chaos surrounding it all confidence

in the German banking system has been lost, a run on the

other banks follows and another nail is hammered into

the coffin of the democratic Weimar Republic. Eventually

the Danat is absorbed into the Dresdner Bank and the branch

will re-open under that banner. But on the day my father

is standing there the old Danat signs are still awaiting

replacement and the branch remains closed to business.

With

that failure and the chaos surrounding it all confidence

in the German banking system has been lost, a run on the

other banks follows and another nail is hammered into

the coffin of the democratic Weimar Republic. Eventually

the Danat is absorbed into the Dresdner Bank and the branch

will re-open under that banner. But on the day my father

is standing there the old Danat signs are still awaiting

replacement and the branch remains closed to business.

Look up at the first floor,

above the empty branch and the cabbie's head; and at the

second floor too.

These two floors contain a business, Grünthal, Sorensohn & Co. It is a tailor's, specialising in women's costumes and coats. We know a little about this business and the families who own it. Their story tells us more about the tragedy of 20th century European history.

The Sorensohns are Jewish. The Grünthals may or may not be; many bearers of the name in Berlin at this time are not, although because of their business association the Sorensohns' partner probably is. But such a distinction is, so far, of little importance in a civilised country in the first third of the 20th century.

The Sorensohns, a family with an uncommon name, have been in Berlin for many decades. They live mainly in the Charlottenburg and Wilmersdorf areas of the city, to the west. In the 1870s there is a tailor of that name in Sebastianstrasse and the family has probably been here in Berlin for far longer. At the turn of the 20th century the record shows a widow as head of the family. By 1912 Benjamin/Benno and Hugo appear, both described as merchants or businessmen. They have been born in Mainz, in 1878 and 1880, respectively. They are brothers and sons of Herz and Sara Sorensohn, Herz having originated from Vilnius, Lithuania. They have an elder sister, Mathilde, b. 1873, again in Mainz. Hugo lives at Helmstedter Strasse 15 with his wife Gertrud. By 1913 he has joined forces with Otto Grünthal and formed Grünthal, Sorensohn & Co., manufacturers of ladies' coats and costumes and based initially at Kronenstrasse 15. The Grünthals have two similar businesses in the same area of the city, one even in the same street.

August 1914 sees the beginning of the Great War. Benjamin Sorensohn volunteers to serve at the relatively late age of 36 and within the first year gives his life on July 3rd 1915. His widow Amalie/Mally continues to live in Charlottenburg where she will stay until the early 1930s. There are children too, Ari (b.1909) and Gershon (b.1915, on the day on which his father dies at the Front). Hugo, on the other hand, remains in Berlin during the war, running the business. He and Gertrud have two children, including a son, Heinz (b.1912) and a daughter, Ingrid, who is born on July 9th 1915, just six days after Benjamin's death. But in about 1922 Gertrud too is left a widow at the age of 44, and the seven-year-old Ingrid fatherless. They continue to live in Helmstedter Strasse but now next door at No. 14.

For several years Gertrud is listed as a widow. In 1929 we see her described as a businesswoman. Perhaps the economic turmoil in Germany in the 1920s, including rampant inflation which destroys personal savings, has forced her to work. It is reasonable to assume that she is now active in the family business.

Grünthal, Sorensohn & Co. appears to survive all the economic upheavals. By 1931/1932 it is shown as being in the Charlottenstrasse, Nos. 29 and 30 where we are looking at it now. We can see from the picture that it occupies a large corner site, partly in Charlottenstrasse and partly in Kronenstrasse where it was originally founded. By the time my father is standing on the other side of the street the windows have only borne the company name for a year or so. The business is obviously significant: it occupies at least two floors of the substantial building and its location is a prime one. It will continue to be listed here for several years to come, in fact for the remainder of its existence.

But by the time of the picture difficulties will soon be arising for the business. The day on which my father is standing there in the sunshine is one in the summer of 1932. In the following January, the German people, disillusioned with the perceived shortcomings of their democratically elected government, cast their votes for a party who will later reveal themselves as a group of criminals, capable of ruining Germany and much of Europe within 12 short years. The accession to power of the Nazis in January 1933 encourages and legitimises an increasing hatred and isolation of Jewish people. The 1935 Nüremberg laws start the process of formalising this: relationships, including marriage, between a Jew and a citizen of German blood are forbidden; there are restrictions on whom a Jew may employ within the household; and a Jew is not regarded as a citizen of the German Reich and is effectively disenfranchised. During this period, Gershon, Amalie's son, leaves for Denmark in 1934 and eventually, after a return home in 1936 to see his mother, goes to Israel. Ari, her other son, leaves Berlin in 1935 for the USA where he lives initially with his aunt, Amalie's sister, and where another sibling of Amalie's is now located, Emil. Ari marries and has three daughters in due course, one of them named Ingrid, no doubt after his cousin.

Gertrud is still listed as a businesswoman in 1933. But in the following two years she disappears. Perhaps she has moved out of the city, possibly even abroad. In 1936 she is back, living in the same area at Aschaffenburger Str. 2. She is now shown again as merely "widow"; she has probably retired or perhaps it is sensible in these difficult times not to publicise the fact that she is still active in business. She lives there for two years and then moves again, back into the Helmstedter Strasse, now at No. 1, where she is listed until 1939. In that year her son, Heinz, dies in Berlin at the age of 27. Then she and Ingrid disappear again, for the last time.

Meanwhile the firm of Grünthal, Sorensohn & Co continues to survive through the 1930s, still located at the Charlottenstrasse address. One can imagine the growing difficulties under which it labours: the increasing pressure on it to aryanise itself, official encouragement of all "good" German citizens to boycott Jewish businesses. Finally it succumbs. On October 12/13th 1938 it is sold by the "Union" Auction Rooms of Leo Spick, Berlin, a company which will survive into the 21st century. Less than a month later, on the night of 9/10th November later to be known as Kristallnacht (the night of broken glass), the authorities unleash a period of terror on Jewish citizens: businesses, places of worship and homes are looted by Nazi thugs and often wholly destroyed, individuals are murdered, beaten and imprisoned. Later the Jewish community has to pay one billion marks for the damage.

In the 1939 lists of companies, Grünthal, Sorensohn & Co. no longer appears. Nor do the other Grünthal companies. Five years of state oppression and intimidation have been successful. More acceptable names now ply their trade in the clothing business at Charlottenstrasse 29, 30: Brückner, Fuchs and Schubert. At some stage during this period members of the Grünthal family emigrate to Buenos Aires and in March 1939 Amalie and some close family members board a steamer in Hamburg bound for New York.

At some stage in 1938 or 1939 Gertrud and Ingrid flee the persecution, initially to Brussels and later to France where after the invasion of June 1940 they find themselves again in the hands of the Nazi regime. Back in Berlin the Wannsee Conference takes place in January 1942 when a group of officials under the chairmanship of Reinhard Heydrich agree the bureaucratic details of the "Final Solution". The effects of these decisions are rapidly felt throughout occupied Europe. During the summer Gertrud and Ingrid are imprisoned at the transit camp at Drancy, on the outskirts of Paris. On September 18th 1942, the German authorities, with the help of the French Police who still nominally control the camp, make their final expression of gratitude for the contribution the Sorensohn family has made to German society in times of peace and war: together with about one thousand others the two women are herded on to a train at Drancy Station, as part of Transport No. 34 bound for Auschwitz. They will not return.

But there is a happy postcript to this otherwise sad story. As we have seen Amalie and her sons all left Berlin during the 1930s. Their route has been a tortuous one. It runs from the oppression of a Nazi-ruled Berlin, via the freedom of the U.S.A and Israel, and it has taken 80 years. But today, in the second decade of the 21st century, Berlin is the city in which the great-great-grandchildren of Benjamin and Amalie have been born and will probably spend their lives. |

But

as my father stands on this sunny, peaceful street, the horrors of the coming years lie in the future. He has probably not noticed

much of the background, as we can later do, which shows

Grünthal, Sorensohn's windows open because of the

summer heat. Behind them Gertrud Sorensohn is probably working and

perhaps even the teenaged Ingrid too. And whilst he is

undoubtedly conscious of the current trend of European

history, for he is a thoughtful and intelligent man, he

can as yet have no idea of where it will lead and the

millions of individual tragedies which will result.

But

as my father stands on this sunny, peaceful street, the horrors of the coming years lie in the future. He has probably not noticed

much of the background, as we can later do, which shows

Grünthal, Sorensohn's windows open because of the

summer heat. Behind them Gertrud Sorensohn is probably working and

perhaps even the teenaged Ingrid too. And whilst he is

undoubtedly conscious of the current trend of European

history, for he is a thoughtful and intelligent man, he

can as yet have no idea of where it will lead and the

millions of individual tragedies which will result.

Let us now leave the Charlottenstrasse

for a few moments and go forward with my father five or

six years, to 1937 or 1938 when he makes his last pre-war

trip to Germany. The bleakness of the future will still

have been  unimaginable

to him, although perhaps he is starting to sense the trends.

By then he has a train-mad two-year-old son, me. He brings

back with him one or two photographs of stations and massive

steam locomotives for my benefit. There would have been

more but the others are torn from the camera by an angry

official who objects to someone taking pictures of railway

sidings. My father's schoolboy German is somehow sufficient

to deflect a more serious sanction. He returns home and

spends much of the winter of 1938/1939 building an air-raid

shelter in the garden, months before Hitler's invasion

of Poland and to the amusement of his neighbours.

unimaginable

to him, although perhaps he is starting to sense the trends.

By then he has a train-mad two-year-old son, me. He brings

back with him one or two photographs of stations and massive

steam locomotives for my benefit. There would have been

more but the others are torn from the camera by an angry

official who objects to someone taking pictures of railway

sidings. My father's schoolboy German is somehow sufficient

to deflect a more serious sanction. He returns home and

spends much of the winter of 1938/1939 building an air-raid

shelter in the garden, months before Hitler's invasion

of Poland and to the amusement of his neighbours.

But by the time he returns

to Germany in the icy December of 1945 he, and the rest

of the world, are more than aware of how events unfolded.

He is now leading an Allied war reparations

team, assessing German industrial equipment and deciding

which of it should be shipped to England. He undertakes

this trip in the uniform of an honorary lieutenant-colonel

of the British Army and again he records for posterity the sights he sees.

At some stage on a journey through

Northern Germany from one devastated factory to another,

he and his companions stop at the roadside and photograph

each other. This time the background of the  picture is

selected deliberately and with care. It is an area of

snowy, rough grass beyond which lies a barbed wire fence

and on the other side of that a number of substantial

buildings. They are not at all temporary as one might

expect from the heartbreaking newsreels and newspaper images of the previous April; rather

they are permanent and, as my father notes, designed to

be used for many generations to come. To the right of

the group is a sign denoting the name of the place: Belsen.

picture is

selected deliberately and with care. It is an area of

snowy, rough grass beyond which lies a barbed wire fence

and on the other side of that a number of substantial

buildings. They are not at all temporary as one might

expect from the heartbreaking newsreels and newspaper images of the previous April; rather

they are permanent and, as my father notes, designed to

be used for many generations to come. To the right of

the group is a sign denoting the name of the place: Belsen.

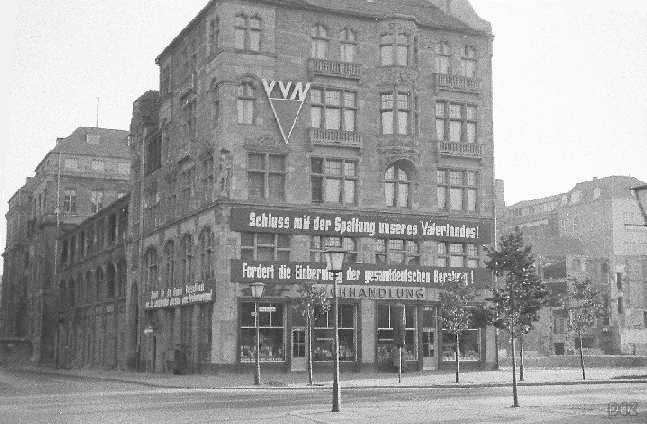

As for Berlin itself, my

father never returns there after the 1930s. The city

will endure bombing raids from the middle of 1940, of

increasing intensity and with few periods of respite,

until the spring of 1945 when it is further devastated by  the Soviet artillery. The Charlottenstrasse will,

like the rest of central Berlin, be largely destroyed

and in the last days of April 1945 the Red Army will overrun

it. Thereafter this stretch of the street will form part

of the Soviet Sector of the city, a sad and fairly desolate

area as this 1953 image of a nearby, surviving building,

Charlottenstrasse 46, suggests. The boundary with the

western sectors will lie less than a couple of hundred

metres down the street in the direction my father is looking

in happier times. For a few years Berliners living in

the three other sectors - the British, American and French

- will be able to travel freely to this part of Berlin,

to work or to visit friends and relatives. But in 1961

the boundary will evolve into an ugly, permanent barrier

in the form of the Berlin Wall, splitting the city, and

Charlottenstrasse, into two and preventing most Berliners

from setting foot in the other half of their city for

the next 28 years. Many from East Berlin will die, trying

to escape to the West, shot by their fellow countrymen.

During this period, the ruins of the building

we have been looking at will be cleared away and a large

new hotel built, in a style far removed from the original

and facing a

the Soviet artillery. The Charlottenstrasse will,

like the rest of central Berlin, be largely destroyed

and in the last days of April 1945 the Red Army will overrun

it. Thereafter this stretch of the street will form part

of the Soviet Sector of the city, a sad and fairly desolate

area as this 1953 image of a nearby, surviving building,

Charlottenstrasse 46, suggests. The boundary with the

western sectors will lie less than a couple of hundred

metres down the street in the direction my father is looking

in happier times. For a few years Berliners living in

the three other sectors - the British, American and French

- will be able to travel freely to this part of Berlin,

to work or to visit friends and relatives. But in 1961

the boundary will evolve into an ugly, permanent barrier

in the form of the Berlin Wall, splitting the city, and

Charlottenstrasse, into two and preventing most Berliners

from setting foot in the other half of their city for

the next 28 years. Many from East Berlin will die, trying

to escape to the West, shot by their fellow countrymen.

During this period, the ruins of the building

we have been looking at will be cleared away and a large

new hotel built, in a style far removed from the original

and facing a way from us towards the cathedral.

way from us towards the cathedral.

Only with

the fall of the Wall in 1989 and the reunification of

the city will Charlottenstrasse start to revert to the

sort of street my father saw fifty-seven years, and a

lifetime, earlier. Then the hotel will become the Berlin

Hilton. In place of the Danat Bank branch on the corner

we shall have the hotel's parking garage and above it,

not a tailor's workshop but the bedrooms of businessmen

and tourists visiting a once again peaceful city. And

here is the corner again, photographed on October 26th

2007.

Eighty years after

that sunny day in 1932, who will now think about that

street as it was, and the buildings which stood on it

and the people who lived and worked within them? And about

a couple of Birmingham businessmen, pausing for a moment to be photographed

before they go about their business or start their sightseeing? Only you and I, perhaps,

just for a minute or two.....

CM ......

November 2007 (revised January 2013)

Text and

images © CM 2007

except: 1953 and 2007 images © Dieter E. Zimmer 2007

More images of the stroll around Berlin on that summer's day in 1932, of railway locomotives in the late 1930s and of Hamburg and Northern Germany in the bitter December of 1945 can be viewed on this further page.

Wartime memories and information relating to Birmingham and adjacent towns and villages are listed in this Home Guard website here.

Acknowledgements:

Grateful acknowledgement is made to Dr. Dieter Zimmer

for permission to use the 1953 and 2007 images and for

other invaluable information; Mr. Alan Teeder of the Riley

Owners' Club; members of the

excellent

Birmingham History

Forum; the Zentral- und Landesbibliothek Berlin; the

Landesarchiv, Berlin; Yad Vashem; M.R. of Berlin who is related to the Sorensohn family; and various other sources.

(An interesting set of 1952/3 images of Berlin can be

seen on Dr.

Zimmer's website)

If you have reached

this page via the Birmingham History Forum, you can

return there using the link below.

L2