STREETLY,

STAFFORDSHIRE

MEMORIES

(1936 - 1961)

A WEEKEND AT THE

SEASIDE

by Chris Myers

|

A WEEKEND

AT THE SEASIDE

Nothing

could be better than this. Nothing.

I’d been

to the seaside before. Of course I

had. Lots and lots of times. Mummy

had told me. But the last time was

ages ago and I could only just

remember a stony beach because I'd

been there last August and now it

was another year and it was May. A

Friday. Nine months is a long, long

time when you’ve only

just had your fourth birthday.

Here was me, in the summer of 1938,

nearly two years ago now, on a beach

in Devon and I was probably feeling

the same feelings - but I can't

remember anything about it. I’d been

to the seaside before. Of course I

had. Lots and lots of times. Mummy

had told me. But the last time was

ages ago and I could only just

remember a stony beach because I'd

been there last August and now it

was another year and it was May. A

Friday. Nine months is a long, long

time when you’ve only

just had your fourth birthday.

Here was me, in the summer of 1938,

nearly two years ago now, on a beach

in Devon and I was probably feeling

the same feelings - but I can't

remember anything about it.

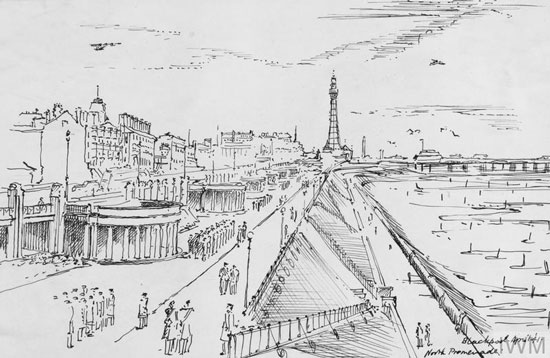

But

here I

was at the seaside again, now,

today, but this time I was standing

on another beach, a sandy one, which

stretched for miles and miles. There

was more open space than I had ever

seen before, enough to make me

breathless with wonder at the

vastness surrounding me. And the sea

stretching away for ever, blue and

sparkling. When I looked out over

it, the edge where it met the sky

was curved, which proved to me that

the earth was round, just like my

big sister had told me. Like a huge

orange, she’d said. She knew about

lots of things. It was a pity she

was so bossy-abouty. But at least

she was now helping me make a

sand-castle while our mum and dad

and elder brother lay back on the

sand in the afternoon sunshine,

relaxing after the long journey,

their hands behind their heads. They

were all squinting at the distant

horizon and seemed completely

wrapped up in their own thoughts.

The

sand-castle was finished. It only

needed the little tissue-paper flags

which had been bought especially

from a kiosk on the promenade, just

behind the beach. No sooner than I

had opened the packet, the dozen

little flags inside, which were the

national flags of more countries

than I knew existed, were grabbed

out of my hand by a violent gust of

wind, scattering and disappearing

totally, utterly, irretrievably.

This disaster was so unexpected and

so complete that I was numbed with

shock and did not even cry.

In

fact I was surprised at my own

bravery. Still dry-eyed I soon found

myself trotting along the promenade

in the midst of the family, licking

a consoling ice-cream. I didn't

notice the lines of RAF men there,

practising how to stand to attention

and handle their rifles and march up

and down - my big brother told me

about all that a long time

afterwards. And also about why the

weekend ended up as it eventually

did. In

fact I was surprised at my own

bravery. Still dry-eyed I soon found

myself trotting along the promenade

in the midst of the family, licking

a consoling ice-cream. I didn't

notice the lines of RAF men there,

practising how to stand to attention

and handle their rifles and march up

and down - my big brother told me

about all that a long time

afterwards. And also about why the

weekend ended up as it eventually

did.

But what

I did see was something absolutely

wonderful, a toy I’d never seen

before, and that was a

multi-coloured windmill on the end

of a stick. It was tied to another

toddler's pushchair and was whizzing

around furiously in the breeze as it

passed by. The owner of the

desirable object was not even

looking at it and, unbelievably,

seemed to have an expression of

intense boredom on her silly face.

Perhaps even smugness. A sense of my

own recent loss and a desire to own

such a beautiful thing overwhelmed

me. Two quiet requests to my parents

were followed by a more forceful

plea which in turn led to a tantrum

which was one never to be forgotten.

But despite standing in the

grown-ups' path, barring their way

and screaming as loudly as I was

able, no windmill was going to be

bought for me and the world appeared

wholly bleak and cruel.

At

breakfast the next morning my

outlook had long since improved,

with thoughts of windmills and lost

flags dismissed and the world again

full of promise. I had the vague

impression that my cheery mood

contrasted with that of the other

four. They seemed to have lost their

high spirits of the previous day but

I had no idea why. I finished my

boiled egg and, bored with a serious

conversation I could not follow,

left them to their muttering and

slipped off the tall hotel chair.

Then down to the floor and under the

table where an exciting new

territory opened up. As I crawled

amongst the legs, both human and

oak, I felt some surprise that for

once no notice was being taken of

such behaviour in a public place. By

the time that I had re-emerged,

tired of this normally forbidden

activity, the discussions had ceased

and I was told, gently, that they

had all decided it would be better

to return home that morning, rather

than to stay on to Sunday as they

had intended. Daddy would go and get

the car filled up while the rest of

us had a last look at the sea.

On

the promenade I was persuaded,

against my better judgement, to

accept the treat of a ride on a

children’s roundabout (a bit like

this one). I was lifted into a small

car, painted pink. I grasped the

steering wheel and was overcome with

self-consciousness as I found myself

going round and round in front of a

ring of grown-ups. These mums and

dads all seemed to be watching the

children on the roundabout ever so

intently. But I knew that it was

just me they were all looking at. I

bowed my head, overcome with

self-consciousness, and sat for an

eternity with my eyes focused on a

sheet of metal in front of my knees

beyond the steering wheel. It was

like a tiny, enclosed world, painted

pink, just like the maps of the

British Empire, and flecked with

rust. Round and round and round.

Finally and to my immense relief the

ride came to an end. I was lifted

out of the car and then I snuggled

up to Mummy where at last nobody

seemed to be looking at me. She put

her arm around me and seemed to

press me to her side even more

closely than she normally did. On

the promenade I was persuaded,

against my better judgement, to

accept the treat of a ride on a

children’s roundabout (a bit like

this one). I was lifted into a small

car, painted pink. I grasped the

steering wheel and was overcome with

self-consciousness as I found myself

going round and round in front of a

ring of grown-ups. These mums and

dads all seemed to be watching the

children on the roundabout ever so

intently. But I knew that it was

just me they were all looking at. I

bowed my head, overcome with

self-consciousness, and sat for an

eternity with my eyes focused on a

sheet of metal in front of my knees

beyond the steering wheel. It was

like a tiny, enclosed world, painted

pink, just like the maps of the

British Empire, and flecked with

rust. Round and round and round.

Finally and to my immense relief the

ride came to an end. I was lifted

out of the car and then I snuggled

up to Mummy where at last nobody

seemed to be looking at me. She put

her arm around me and seemed to

press me to her side even more

closely than she normally did.

We walked

back to the hotel where Daddy had

already put the suitcases in the

car. As we drove off I gave the sea

a final wave, as Mummy told me to

do, and promised it I would come

back as soon as I could. I nestled

up beside my sister on the rear seat

and looked sadly out of the window

at the houses and shops which lined

the road out of Blackpool.

As we passed a newsagent's there

were some newspaper hoardings outside,

left over from the previous evening.

They told us the headlines of last

night's final edition. If I had been able to read

any of this -

and understand it - it would

have told me:

No one

spoke.

The little black Ford headed

south, towards Birmingham and

Streetly.

Towards home and safety.

**********

|

POSTSCRIPT

The days after our return

home from our weekend away

are frightening indeed - but

not to me, who is cocooned,

protected, and so,

thankfully, knows nothing of

them.

We get back to Streetly on

the Saturday afternoon. By

the following Tuesday,

Rotterdam is being heavily

bombed and German forces are

pouring into eastern France

- "Blitzkrieg", lightning

war, the frightening new

tactic of fighting. In the

evening, the Minister of

War, Anthony Eden, announces

on the wireless the

formation of a new defence

force, the Local Defence

Volunteers (soon to be

renamed the "Home Guard").

My father volunteers

immediately, together with

dozens of other Streetly and

Little Aston men, many of

whom are survivors of the

Great War and whose memory

of war is still recent and

fresh and ghastly. They are

joined very quickly by my

elder brother who has, as

yet, no experience of it.

On Wednesday the Dutch Army

surrenders. On Friday

Brussels falls.

The following Monday sees

the Germans reaching the

Channel coast, cutting the

Allied armies in two. The

British Army is in retreat

towards the port of Dunkirk.

Miraculously the German army

halts for a day or two in

order to re-group and the

Luftwaffe takes over the

role of attacking the

hundreds of thousands of

troops being forced back

into the sea.

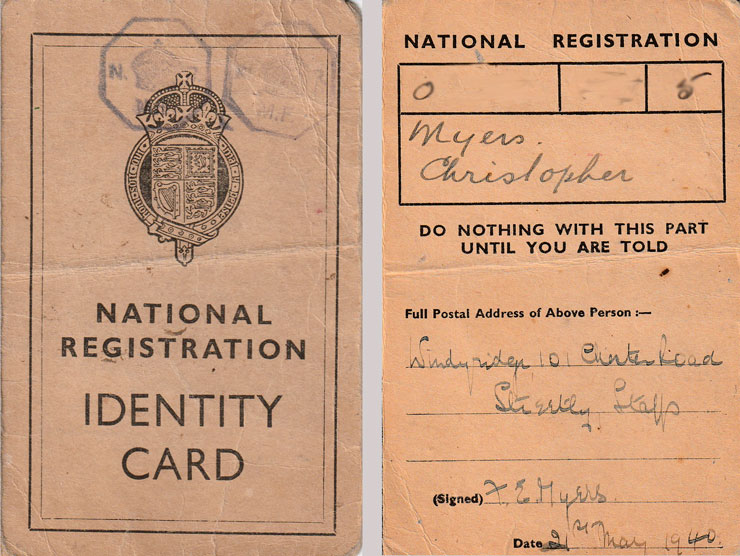

And finally, on Wednesday,

May 21st, ten days after our

curtailed weekend by the

seaside, my mother sits down

at the dining table to fill

out a small buff-coloured

form. As I look now at that

little object, 84 years

later, I visualise her on an

occasion such as this,

leaning forward to dip her

blunt-nibbed pen into the

bottle of Stephens ink and

then, ever so carefully,

filling in the information

which has to be included. As

is always the case when she

is writing something

important, the tip of her

tongue is in the corner of

her mouth as she gives her

full concentration to the

task in hand and the

avoidance of any error. A

quick check that the address

information is correct, the

pen is laid own, a dab of

blotting paper and the job

is done.

|

Within days, by June 3rd,

the miracle of the Dunkirk

evacuation is completed but

during the month things get

ever worse. On the 10th

Italy declares war on us,

Paris falls on the 14th and

France surrenders on the

21st making its entire

Channel coastline available

to invasion forces and

behind it a string of

Luftwaffe bomber bases

within range of all the

British Isles.

I

think of my parents and what

was going through their

minds at this time as they

faced this total disaster

and a new, terrifying,

ongoing threat. Every

Streetly family, every

family in the land, was in

the same position. WHAT must

it have been like to be

someone who was responsible

for children at that time?

How would any of us have

coped with it all?

Perhaps it does none of us

any harm to think of these

things, just very

occasionally.

CM....30 June 2024

|

**********

(Main article originally written in 2003 and

remembering Friday and Saturday, 10/11th May 1940)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Please see INDEX page for

general acknowledgements.

Grateful acknowledgement is also made to:

-

The Imperial War Museum (sketch of

North Promenade)

- Blackpool Gazette

(Road scene)

- The British Newspaper Archive

(Newspaper headlines)

- family members

This

family and local history page is

hosted by

www.staffshomeguard.co.uk

(The Home Guard of Great Britain,

1940-1944)

All

text and images are, unless

otherwise stated, © The Myers Family

2024

|

INDEX

Home Guard of Great Britain

website

|

|

INDEX

Streetly and Family Memories

1936-61

|

L8A3

June 2024

-

© The

Myers Family 2024

| |