Lieutenant WILBUR ARNOLD JOHN

Sussex Yeomanry and 206 Sqdn., R.A.F.

|

Lieutenant Wilbur Arnold John (1895-1918) joined the Royal Flying Corps in early 1918 after service in the Sussex Yeomanry.

During his short period in France as an observer with the  Royal Air Force (into which the R.F.C. had translated itself on April 1st), his comrade and tent-mate in 206 Squadron was 2/Lt. J. Stephen Blanford, D.F.C.

(right). Half a century later Stephen Blanford wrote an article about Wilbur John, entitled "Blind Chance - or the Hand of God?" These are his words: Royal Air Force (into which the R.F.C. had translated itself on April 1st), his comrade and tent-mate in 206 Squadron was 2/Lt. J. Stephen Blanford, D.F.C.

(right). Half a century later Stephen Blanford wrote an article about Wilbur John, entitled "Blind Chance - or the Hand of God?" These are his words:

Like a lot of other young infantry officers in 1918, I answered an RFC appeal for volunteers for air crew duties; and in due course was actually posted to them on the day they were amalgamated with the RNAS to form the RAF, April 1, 1918. After the usual brief training as an observer, I went overseas and joined 206 Squadron on the Western Front towards the end of May, with whom I served until March 1919.

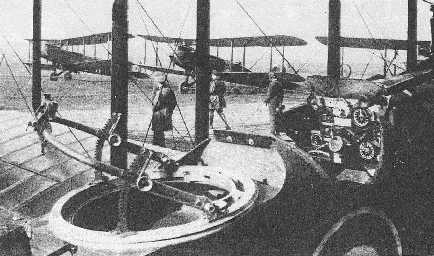

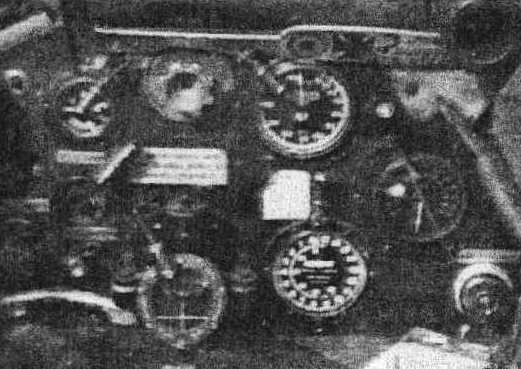

206 Squadron, which had started life as No. 6 Squadron RNAS was during this period the 2nd Army Reconnaissance Squadron, and was equipped with de Havilland 9 two-seaters, which had a performance not greatly inferior to the best  German fighters of that day, and carried the (for those days) heavy armament of three machine guns, one firing forward through the airscrew and two to the rear in a twin mounting operated by the observer (the mountings for which are seen left). We were organised in three flights, each of six aircraft; and as our reconnaissance duties required only one flight at most each day, the remainder of our aircraft were employed on daylight bomb raids. German fighters of that day, and carried the (for those days) heavy armament of three machine guns, one firing forward through the airscrew and two to the rear in a twin mounting operated by the observer (the mountings for which are seen left). We were organised in three flights, each of six aircraft; and as our reconnaissance duties required only one flight at most each day, the remainder of our aircraft were employed on daylight bomb raids.

Midsummer found us on a small airfield at Alquines, between St Omer and Boulogne. By this time I had been awarded my observer's Wing, and had been lucky enough to be assigned as observer to our newly posted Senior Flight Commander, Captain Rupert Atkinson MC, who already had a year and a half of combat experience and was regarded as one of the outstanding two-seater pilots of those days. While serving with us, he added to his MC the DFC and Bar, and the Croix de Guerre, which indicates his quality.

We were under canvas at Alquines, and I shared a tent with another observer, 2Lt W A John, whose pilot was Captain Mathews, C Flight Commander. With the war approaching its climax we were constantly in the air and inevitably had our share of casualties; though these were lighter than might have been expected in view of the fact that we carried out all our missions without any fighter escort; a claim that no other squadron of our type could make.

As a result of these casualties, the lucky air crews moved up the leave roster very quickly, and I myself fell due for leave in mid August after less than three months' active service.

On my return to the squadron at the end of that month, I was saddened to learn that my tent-mate, 2Lt John and his pilot, Captain Mathews, had failed to return from a bombing raid a few days earlier, when their formation had been attacked by the crack German fighter wing known to us as 'Richthofen's Circus', led since von Richthofen's death in April by the subsequently notorious Hermann Goering. Mathews’s and John’s aircraft was last seen going down in a dive with two German fighters on their tail, and John apparently out of action. This was over enemy territory a few miles from the Ypres Salient, but the remainder of their formation were too hotly engaged to see where they actually crashed.

At this time the RAF and the German Air Force had a gentleman's agreement for the regular exchange of information regarding the fate of missing air crews, which they did by means of messages dropped from aircraft and returned a few weeks later. This arrangement worked so well that in the majority of cases the RAF received news about their missing air crews within four or five weeks. However, in the case of Matthews and John no word came through and their fate remained unknown.

At the end of September, the 2nd Army launched their final 'left hook' attack, which broke clean through the German lines on the first day. Like magic, it was open warfare again in Flanders after four long years of trench warfare. By mid October the old Ypres Salient was miles behind our advancing troops; so one afternoon., when bad weather prevented our flying, Captain Atkinson suggested that a party of us should borrow a tender and go on a sightseeing trip to the Salient area, which we knew so well from the air but not at all on the ground.

Leaving our tender on the Menin Road near Hellfire Corner, we walked forward and spent an hour or so wandering about the opposing front line positions, littered with the wreckage of four years' fighting. It was a scene of utter devastation, never to be forgotten. In addition to the abandoned guns, derelict tanks and battered pillboxes, there were several crashed aircraft which we examined with particular interest, though none of them were DH9s. Then, just as we turned to go back to the tender, I happened to notice some little way off a familiar looking tail fin sticking up beyond a slight rise in the ground behind the old German front line positions. I drew my companions' attention to this and suggested we should take a look at it; but they demurred, saying it was getting late and they had seen enough. At this juncture I suddenly became conscious of an inexplicably strong curiosity about it, and managed to persuade Rupert Atkinson to accompany me over to the crash while the others went back to the tender.

On reaching the wreckage, we saw that it was indeed a DH9, and moreover that on the pilot's instrument  panel there was fixed a painted wooden board bearing various symbols and words (including cross, cockade, question mark etc., seen right - above the instruments, at top right), a gadget made in the squadron to enable the pilot to communicate quickly with his observer in emergency without wasting time in shouting (there was no intercom in those days). I daresay other two-seater squadrons used similar things, but the pattern of this one was all too familiar and Atkinson exclaimed 'I swear this was one of our busses.' And then, walking round the wreck, we came on a rough wooden cross, half hidden by the torn fabric of a wing; on the cross were some German words written in indelible pencil. panel there was fixed a painted wooden board bearing various symbols and words (including cross, cockade, question mark etc., seen right - above the instruments, at top right), a gadget made in the squadron to enable the pilot to communicate quickly with his observer in emergency without wasting time in shouting (there was no intercom in those days). I daresay other two-seater squadrons used similar things, but the pattern of this one was all too familiar and Atkinson exclaimed 'I swear this was one of our busses.' And then, walking round the wreck, we came on a rough wooden cross, half hidden by the torn fabric of a wing; on the cross were some German words written in indelible pencil.

Fortunately, Atkinson could speak German well and he translated the inscription for me, which ran roughly as follows: 'Here lie 2Lt W A John and his pilot, English Airmen. killed in air combat - August 1918, RIP.'

I cannot now recall the precise date, but it would have been about August 27 or a day or two later, based on the known date of my return from leave, September 1. To clinch the matter, we noted down the serial number of the engine, and the approximate map reference, and later reported our find to the Squadron.

Thus Mathews and John had nearly - so very nearly - won their way back to our lines and safety, when they were finally shot down and killed. The position of their crash suggests the probable explanation as to why no news of their fate had been received from the German Air Force, namely that the Front Line troops who buried them there and erected the cross either became casualties themselves shortly afterwards, or were moved elsewhere the same night, and so never had a chance to report the incident to their HQ.

But who can suggest a satisfactory explanation of what it was that drew my footsteps so unerringly to the one spot in a hundred square miles of battlefield where my tent-mate and his pilot met their end and lay buried? Was it merely blind chance ... or the Hand of God? |

WILBUR'S CHILDHOOD AND YOUTH

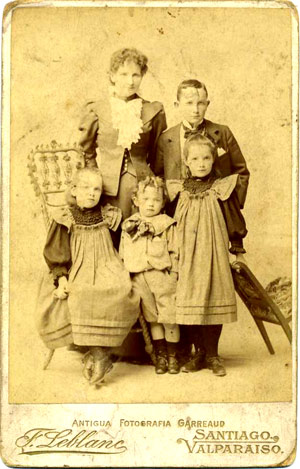

Wilbur John was born in Valparaiso, Chile, in 1895. Wilbur John was born in Valparaiso, Chile, in 1895.

On his mother's side the family had its origins in Scotland, moving to Newcastle in the early 1800s. His maternal grandfather, John James Keil, sailed with his wife to Chile where he was involved in the building of railways. They had six children, one of whom was Wilbur's mother. She in turn went on to marry Richard John, a Welshman who was living in Chile with his brothers, breeding horses. They had four children of whom Wilbur was their youngest, born in Valparaiso. Images of the family survive from almost 110 years ago, showing the children with the mother and on the same occasion as a group on their own:

By all accounts it appeared that the family led a privileged life. Wilbur's sisters had tutors and in around 1907 the girls and Wilbur found themselves in Germany with their mother, Mary Keil de John

(shown, right, in Berlin at the time) learning languages and music and enjoying the social life which included grand balls. Wilbur himself, then aged about 12, was photographed in Berlin too

(left). By all accounts it appeared that the family led a privileged life. Wilbur's sisters had tutors and in around 1907 the girls and Wilbur found themselves in Germany with their mother, Mary Keil de John

(shown, right, in Berlin at the time) learning languages and music and enjoying the social life which included grand balls. Wilbur himself, then aged about 12, was photographed in Berlin too

(left).

Wilbur spent eight years in Europe completing his education and then returned to Valparaiso to enjoy life as a young man...........

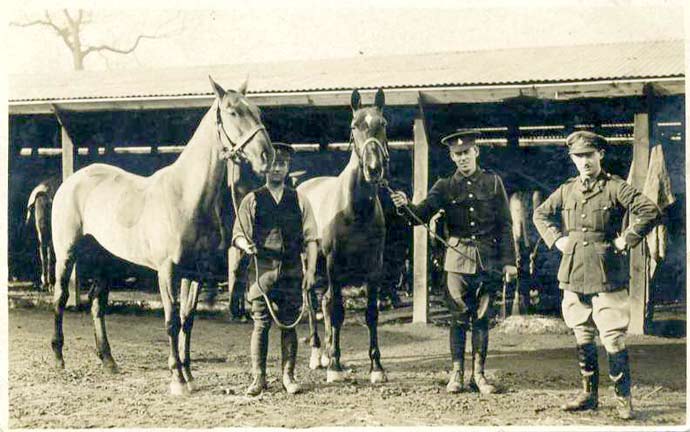

.......which clearly involved, amongst no doubt much else, horses and polo.

WILBUR'S WAR SERVICE

Wilbur had not been back in Valparaiso for long when war broke out in Europe in August 1914 when he was about twenty. He volunteered immediately for service, leaving with the first contingent to return to England to enlist. After training with the Inns of Court Regiment he received his commission in the spring of 1915 and was gazetted to the Sussex Yeomanry. The involvement with horses was by means at an end as the following image shows.

In another image, most probably from 1915 like the one above, he is seen at the front of the group of regimental officers

(right),

photographed at an unknown location, probably in England

during training but possibly in France. In another image, most probably from 1915 like the one above, he is seen at the front of the group of regimental officers

(right),

photographed at an unknown location, probably in England

during training but possibly in France.

Being a good linguist, he was advised to join the Intelligence Corps and after completing his course with merit he obtained an appointment in the intelligence department of the Northern Army. In September 1915 he was sent to France and was attached to the Seventh Corps and completed his final course in the first firing line with the 1st/6th Staffordshire Regiment.

(This is likely to have been

the assault on the Hohenzollern Redoubt in mid-October during the Battle of Loos. The 1/6th North Staffs were 3rd/4th wave of attack, whilst the 1/5th North and South Staffs took the main damage going over the top first).

In the following January he was attached to the 18th Corps. His commanding officer wrote: “He was in the Battle of Arras and the third Battle of Ypres. I found him a most useful intelligence officer. He was particularly good in outdoor work and on various occasions showed great coolness under fire and was always able to furnish me with good reports. I was always very pleased with him and his work”.

Desiring more active duties, Wilbur decided to transfer to the Royal Flying Corps in January 1918 and returned to England for training. He is shown

(left) by the side of an Avro 504 training aircraft at an unknown location together with other personnel. The latter are dressed in R.F.C./R.A.F. uniform, suggesting that they had entered the service direct, in contrast to Wilbur who continued to use, as was fashionable at the time, the uniform of his Army regiment. He completed the course for Observer in July 1918, by which time the R.F.C. had become the Royal Air Force. He was posted to France where he joined 206 Squadron. Desiring more active duties, Wilbur decided to transfer to the Royal Flying Corps in January 1918 and returned to England for training. He is shown

(left) by the side of an Avro 504 training aircraft at an unknown location together with other personnel. The latter are dressed in R.F.C./R.A.F. uniform, suggesting that they had entered the service direct, in contrast to Wilbur who continued to use, as was fashionable at the time, the uniform of his Army regiment. He completed the course for Observer in July 1918, by which time the R.F.C. had become the Royal Air Force. He was posted to France where he joined 206 Squadron.

206 Squadron was based at Alquines, Pas-de-Calais at that time and before April 1st had been known as No. 6 Squadron R.N.A.S. It was equipped with the DH9 aircraft, a capable machine blighted by poor engine reliability. As Stephen Blanford has mentioned above, the Squadron's responsibility was for air reconnaissance and bombing missions. Below is one of the surviving DH9 machines photographed about six months later at Bickendorf, near Cologne, where the squadron was sent shortly after the Armistice as part of the Army of Occupation.

On arrival at the squadron Wilbur was assigned to a flight commander, Captain Mathews, as his observer. By a remarkable coincidence – or perhaps this was the reason for the close association between the two men – John Waldron Mathews had also come from South America in 1915 to enlist at the age of 24, abandoning his profession there which is listed as “sheep farmer”.

Regrettably Wilbur’s operational flying career was very brief. It is not clear how many missions he completed with Captain Mathews but that of August 1st, 1918 was to be the last. He and his pilot were briefed for an operation in the Ypres sector and took off with several other aircraft at 0640 hrs in a squadron DH9, s/no. D-2855. They failed to return from this mission. At first, and for some time, they were posted as missing; later they were reported as killed in action having been brought  down at probably around 0840 hrs. This confirmation would undoubtedly have come as the result of Stephen Blanford’s efforts many weeks later which he described above. (According to another contemporary account, the discovery was almost certainly made on Sunday, October 20th when a group of nine officers undertook this excursion to Ypres and the surrounding devastated countryside). Wilbur and Capt. Mathews were the victim of either Lt. L. Beckman of Ja 56 whose career record of enemy aircraft destroyed amounted to eight, or Lt. K. Seit of Ja 80 whose tally was five – thus both very experienced and skilful adversaries. down at probably around 0840 hrs. This confirmation would undoubtedly have come as the result of Stephen Blanford’s efforts many weeks later which he described above. (According to another contemporary account, the discovery was almost certainly made on Sunday, October 20th when a group of nine officers undertook this excursion to Ypres and the surrounding devastated countryside). Wilbur and Capt. Mathews were the victim of either Lt. L. Beckman of Ja 56 whose career record of enemy aircraft destroyed amounted to eight, or Lt. K. Seit of Ja 80 whose tally was five – thus both very experienced and skilful adversaries.

Wilbur’s then Commanding Officer (almost certainly Major C.T. Maclaren,

left) wrote: “Your son is a very great loss to my Squadron as although he had been with us only a short time he was proving himself to be a most efficient Observer. In the mess he was a most likeable fellow and he is sadly missed by all…”

But of course the loss felt by Wilbur’s C.O. and his brother officers, at least one of whom half a century later remembered him above and elsewhere with fondness, was as nothing to that felt by his bereaved family, one of the countless families whose life would never be the same after the Great War.

Wilbur’s mother and her daughter visited his grave in 1919, obviously now in a different location from that where he had first been laid to rest, only a year earlier, by retreating German troops with as much reverence as the frantic circumstances allowed. This visit was a harrowing experience, as was to be expected. His mother took flowers in a hat box which she laid on his and the adjoining graves, weeping and talking to him all the time, the grief still fresh and overwhelming. This event was always remembered by Wilbur’s sister, the daughter who accompanied the mother and who many years later recounted it to her own granddaughter. Wilbur’s mother and her daughter visited his grave in 1919, obviously now in a different location from that where he had first been laid to rest, only a year earlier, by retreating German troops with as much reverence as the frantic circumstances allowed. This visit was a harrowing experience, as was to be expected. His mother took flowers in a hat box which she laid on his and the adjoining graves, weeping and talking to him all the time, the grief still fresh and overwhelming. This event was always remembered by Wilbur’s sister, the daughter who accompanied the mother and who many years later recounted it to her own granddaughter.

The mother always wore a locket containing images of her lost son until her own death in 1941 - a tiny thing, measuring hardly 2 inches in height; bearing on the rear face of its front the words "Wilbur. Killed in Air Fight July 31st 1918. Left Valparaiso 1914 to join Territorial Force". The locket then passed into the hands of the daughter who herself never properly recovered from the loss of her brother. Her house was full of photographs of him and, as her own granddaughter recalls, there was a portrait of him on a wall, the eyes seeming to follow a scared ten-year-old girl around the room. After the sister’s death in 1960 the locket passed on to succeeding generations where it still resides, in the safekeeping of the grand-daughter, Wilbur’s great-niece.

Wilbur John lies in the well tended Hooge Crater Cemetery, about 4km from the town of Ieper (Ypres), in the landscape in which he died.

At his side is his pilot, John Waldron Mathews, two men lying so far from their South American birthplace but still together, just as they had been whilst serving their King and Country.

And so with the help of artefact and image is Wilbur John remembered - and with words: words from long ago written by the comrade and friend who found his first resting place and by his Commanding Officer. And now, as well, with the words of his family who ninety years later do not forget his sacrifice.

*************

POSTSCRIPT

As the summer of 1918 turned to autumn and the Allied advance on the Western Front gathered pace, 206 Sqdn. were actively engaged, moving forward from airfield to airfield and like the rest of the Service flying at an intensity which would not be repeated until the Battle of France and the Battle of Britain in another summer twenty-two years later. Fatalities in the Squadron had increased from 7 in July to the appalling level of 11 in August, including Wilbur John and his pilot. Thereafter, thankfully, they reduced, to 2 in September and 2 in October after which the Armistice intervened. And so it is safe to assume that a number of the surviving squadron aircrew who transferred to Cologne in December as part of The Army of Occupation and of whom many images survive would have been known to Wilbur during his short stay with 206.

One of the aircrew who made up the August losses was a pilot, Lt. E. Trevor Evans. His letters home describe experiences and personalities and have been transcribed in an illustrated private publication entitled "With Fondest Love, Trev.", now partly available online on another page of this, the Staffordshire Home Guard website (and also, slightly less accessibly, in the Great War Archive). And Stephen Blanford wrote in considerable detail much later to describe squadron life, operations, people and equipment: his articles are to be found in the Cross & Cockade Great Britain Journal, Vol. 7, No. 4, 1976 and Vol. 8, No. 1 1977.

This web page has been produced in order to commemorate Wilbur John and to assemble the surviving fragments of his life into a form where they can be enjoyed by members of his family and anyone else who can access the page. For convenience it is linked into a website which remembers another group of patriotic men who defended their country a quarter of a century later, Britain's Home Guard - the Staffordshire Home Guard website - which is where you find yourself now. To view the contents of the site, please see the Site Map. |

SOURCES and ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the sources of the above information:

SUSAN LAPHAM of Cornwall (great-niece of Wilbur John)

THE UNKNOWN SUCCESSORS of

J. Stephen Blanford

THE PUBLISHERS of "The Dragon" (the regimental magazine of The Buffs) and of the Cross & Cockade Journal in both of which Stephen Blanford's words and the associated images have previously appeared.

G.M. of Australia, aviation historian.

Jeremy Manners

"WITH FONDEST LOVE, TREV."

(the edited letters home of Lt. E. Trevor Evans, 206 Squadron R.A.F. one

of the aircrew who joined 206 Squadron as

replacements immediately after the death of Wilbur

and his comrade. These letters were published privately by A.P., H.P. and C.M.

in 2004 and available in part online,

here within

this website).

COMMONWEALTH WAR GRAVES COMMISSION and the associated organisation

THE WAR GRAVES PHOTOGRAPHIC PROJECT

|

C.M ...... January 2009

|

|