This is a page within the www.staffshomeguard.co.uk website. To see full contents, go to SITE MAP.

MEMORIES

AND INFORMATION - SHROPSHIRE

Lt.-Col. F. H. LIDDELL, M.C.

(1st

SHROPSHIRE BATTALION,

HOME GUARD)

and

THE GREAT WAR

|

Most men who had survived the Great War kept their

experiences to themselves in later years, unwilling to

discuss them even with close family and preferring to

keep them deeply buried. Few left any written record. Most men who had survived the Great War kept their

experiences to themselves in later years, unwilling to

discuss them even with close family and preferring to

keep them deeply buried. Few left any written record.

Frank Liddell may well have been such a man. He

was a survivor of that conflict and left the Army

after the Armistice with the rank of Major, later

donning uniform again to command the

1st Shropshire

Battalion of the Home Guard. In the Great War he had

enlisted as a private from his Solihull home and had

served with the 15th Battalion of the

Royal

Warwickshire Regiment, one of the "Birmingham Pals"

units. Even though he left no written description of

his life in those years, fragments of his Great War

experience survive in a scrapbook he kept in later

life. One in particular leads us to a glimpse of what

such men went through and how they conducted

themselves in unimaginable circumstances. This

clue dates from 1933, 15 years after the end of

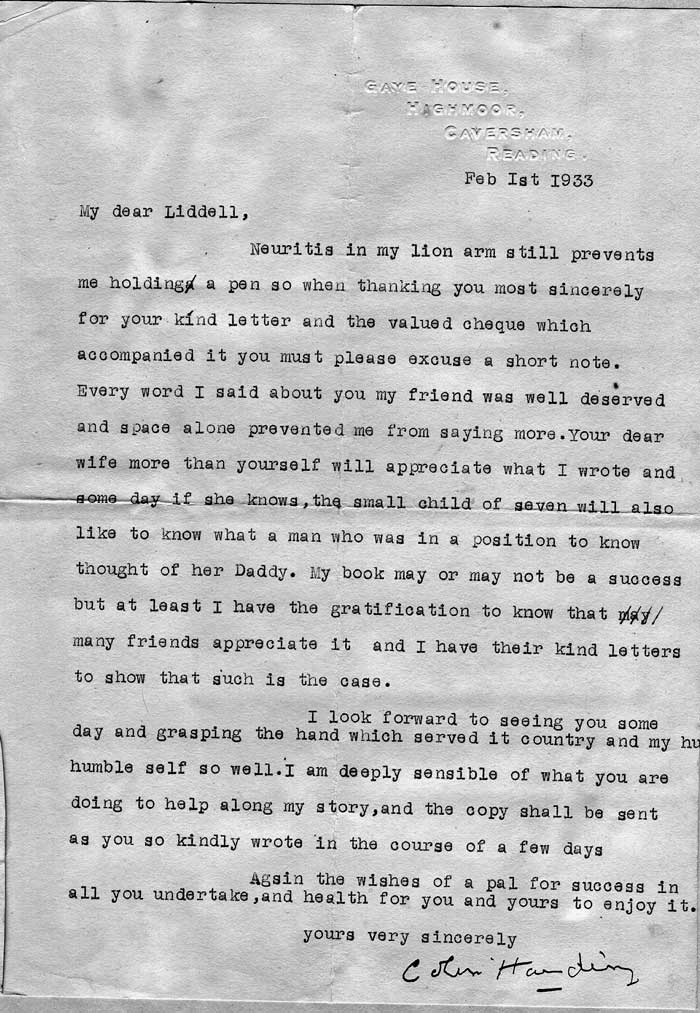

hostilities. It is a letter from a man named

Colin Harding.

The correspondence refers to a book by Colin

Harding which had recently been published, "Far

Bugles", an autobiographical work which describes the

author's experiences - and especially of his

time as Commanding Officer of Frank Liddell's unit,

the 15th Battalion of the R.W.R. Happily, the

copy of this book which Frank had obviously requested

survives within his family to this day. A

transcription of relevant pages follows: they describe a time when

Frank had been commissioned and was serving as

adjutant. They give

a description of his bravery and loyalty

(his name is highlighted) and are quoted at length in

order to give an indication of the conditions and

circumstances which he endured in 1916 as just one

part of his war service.

Colin Harding

describes how the enormous losses incurred by

the British Army in 1915 led to everything

possible being done to hasten up the new army

which Lord Kitchener had promised.

It was in one of these

battalions in the new army that I was given

a command, shortly after I had said good-bye

to my old Regiment, The Second King Edward's

Horse.

I would like

to say a few words as regards the organisation

and personnel of my new battalion. In the

first place nearly every officer and man

hailed from the wonderful city of Birmingham,

and they formed one of the many battalions

which that loyal city had raised for the war.

Starting their training in a well-known park

near to Birmingham, the 15th Warwicks had

under capable instruction made rapid strides

towards efficiency by the time they arrived at

Codford in the late summer of 1915, and on my

arrival at Codford it was with great pleasure

I found the mess full of keen, smart and

well-educated officers.........

The 15th Battalion found itself on the Somme

in July 1916 not long after the fateful first

day of the attack which led to 60,000

casualties......

Although

when my Battalion arrived to participate in

the Battle of the Somme, the fighting was not

so severe as it was on the first day of the

attack, the scene as I shall briefly describe

it was a veritable shambles.

We first

took up a position close to High Wood, where

we were bombarded eventide and early morn, and

by way of a change deluged with "tear shells"

in mid-day. So intense was the enemy's

bombardment that the trenches which we were

supposed to hold were smashed to smithereens

and the losses of our Brigade were enormous.

Owing to the incessant artillery lire, it

was almost impossible to collect or evacuate

our wounded. The dying groans of a gallant lad

shot through the abdomen, waiting to be

removed by the intrepid and overworked

stretcher-bearers is still vivid in my memory.

The cry of a horse who, with blood pouring

from a fractured thigh, with harness dangling

and foaming mouth, rushing mad with pain

hither and thither is ever by me to be

remembered. He, too, poor thing, had also done

his duty and the gun which he helped to drag

vomited death and destruction at close range

on the enemy's lines. Such were some of the

scenes which we endured during the Somme

Battle of July, 1916. Yes, they are ancient

history, but I quote then without hesitation

lest others forget. I use the word "others"

for we who endured them can never forget.

No battalion can stand this carnage more

than 48 hours, hence at early dawn with

bloodshot eyes and haggard mien we who are

left retire to recoup a few miles from the

scene of destruction.

But even away

from the front line we are not immune from

danger as I will show by the sad death of my

groom, and a narrow escape for myself.

We had gone back about four or five miles from

the front for a short rest, and although we

were in trenches, we were supposed to be out

of the reach of the ordinary shelling. Such

being the case, I sent for my horse, which was

stabled a few miles again further back

and it was brought up to me by Doyle, my

groom. My charger was a very brainy mare

devoted to Doyle and Doyle to the horse. In

this instance he rode up his own horse and led

mine, and I had hardly mounted when the enemy

started sending over a casual shell or two. As

my men were resting outside their trenches, as

soon as the shelling commenced I rode round

ordering them to take cover. Whilst so doing,

a shell pitched between the horse Doyle was

riding and my own; Doyle and another man were

killed, also Doyle's horse. The impact threw

me out of my saddle and I was dazed; clinging

to my horse's neck we rushed helter-skelter

until we were suddenly brought to an abrupt

stoppage by a trench. Friends came to my

assistance. I was shaken but not wounded. My

horse was hit but not seriously, but the poor

dear was sadly frightened as was its rider.

God moves in a mysterious way, and why Doyle

and myself did not cross to the Unknown

together I shall never quite understand.

A few days rest and then again we are

holding the front-line trenches, this time

between High and Delville Woods, and the time

is about 4:30 a.m.; and a new day will soon

dawn. Since 10 p.m. we have been taking over

this line from a Devonshire Battalion. The

O.C.of that distinguished unit has said

goodbye to me. He has not slept for many

hours, and with tired eyes and shaky steps he

follows what remains of his Battalion to the

"support lines".

Captain

Liddell,

my indefatigable Adjutant, with notebook in

hand, is jotting down some Brigade Orders

which we have just received, and now informs

the Brigadier over the phone that we have

"taken over", and also informs him that in

doing so casualties have been heavy.

The Commanding Officer of the Battalion which

was to hold the line on our right flank

arrives, distraught and depressed. He informs

me that his Battalion had been decimated on

its way to the trenches which he was to have

taken over, and that the remnants are not to

be found. His Adjutant who accompanies him

breaks down and, sitting by the dugout

entrance, weeps like a child. I have known him

as a strong, gallant man, and such he still

is, but the ordeal of continual shelling with

its horrible result has been too much for him,

as it had been for better and even more tried

men.

I can offer no clue as to the

whereabouts of their Battalion, or what

remained of it, and with a sympathetic

handshake we parted; my friends proceed down

the shattered trench in quest of the remnants

of their lost command, and I to strengthen my

newly acquired position.

Our Brigade

instructions disclose the fact that, in

conjunction with other battalions, we have to

attack tonight.

It is now about 10 a.m.

Enemy shelling has, more or less, ceased.

My Adjutant

and I snatch a few hours' rest and I see my

Company Commanders and give them their

instructions. I find them in deep dugouts

which were created by the enemy. They are 20

or 30 feet deep, and we have to descend many

steps to arrive at the basement; here the

dugouts spread right and left, something like

an inverted letter " T."

It is now

evening ; the hour of the attack is

approaching. Again I am walking round my

lines. I see Captain Gough, whose company has

to lead the attack, with his officers having a

"snack" of food in their dugout. I ask and am

cheerfully informed that they are all ready

for the attack, and I learn that their watches

had been synchronised with Brigade

Headquarters. I wish them good luck and return

to my headquarters.

As the time for our

advance approaches, the enemy bombardment

increases, and our men, although closely

following a devastating "barrage" of our own

guns, fail to reach their objective. More

troops are sent in support, still failure.

Everything is vague and, except for messages

transmitted by orderlies, there is no

communication with the attacking troops. The

enemy bombardment continues. Our guns, not

knowing the state of affairs, are more

subdued. Only a few survivors of this attack

returned. Later, when proceeding to the scene

of action, I met amongst the many wounded a

stretcher bearing my dear friend, Gough, still

smoking his inevitable cigarette, bespattered

with mud, pale as death but cheerful. He had

been shot through the thigh and had a compound

fracture. As we shake hands, Gough gives me a

few heartrending details of the loss of life

and the attack, needlessly apologises for its

failure and passes on. We never met again.

Captain Bill, another of my gallant Company,

was also wounded in this attack,

Later,

another Battalion attacked the position which

previously we had so fruitlessly assailed, and

as I watched it from afar, I saw in broad

daylight the advancing troops leave their

trenches. I saw the hellish shells bursting in

their midst, and men in the throes of death

throwing up their hands towards heaven. In the

distance the scene resembled a scattered swarm

of brown ants without a leader. I saw them

falter, and those who could, retreat, and as I

watched, I wondered whether all this carnage

was worthwhile and I still wonder.

Depressed and fearfully reduced in strength,

my Battalion now proceeds to vacate its

trenches, handing over the responsibility of

keeping the flag flying to other equally good

and valiant troops. We proceed to Villers

Campsart, where, figuratively speaking, we

"lick our wounds" and try to find solace in

the thought that we had played the game.

Alas! the Battalion is not the same as

when scarce a year ago I entrained them at

Wylye Station. All my old Company Commanders

had been casualties. Captain Bill and Captain

Edwards, both excellent and most loyal

officers, had been wounded and many of my

Platoon officers not less gallant, had either

been killed or wounded. But what of the men?

That thought crosses my mind as I inspect the

Battalion for Church Parade at Villers, for

the majority of the faces I see are not those

who loyally and voluntarily came forward early

in 1915 to do their duty.

And what

about myself through all these trying times?

Candidly, the pace is beginning to tell. I

still feel the effects of my lion accident

many years ago. Often at night my fitful rest

is disturbed by pangs, which at times I find

more trying to bear than a "circus"

bombardment by the enemy, and speaking of

incidents which have happened more recently,

the shell that bowled Doyle over and nearly

outed me, has mentally left its mark. I am not

getting jumpy, but at times horribly tired and

sad when I think of the losses we have

suffered and the little we have gained as

compensation.

I am blessed with the

best of Adjutants in the person of a

diminutive but brainy Birmingham business man,

who is as thorough in all his war Battalion

duties as he was punctilious in his business

career.

Captain

Liddell was with the Battalion at the

early stages of the war, and since then

consistently and diligently without fear or

without favour, in sunshine and in rain, in

the trenches and out, carried out his duties

with a pertinacity and cheerfulness that might

well be emulated, but cannot be surpassed, by

any Adjutant in the British

Army...............

On a Sunday at the

end of August, after a period of rest, the

Battalion receives instructions to move and

join up with the French who are holding the

line somewhere northwest of Maurepas.

To get there we had to pass Maricourt,

but, alas, it could not now be recognised as

the Maricourt where, more than a year ago, I

rested with the King Edward's Horse. I

remember that journey, alas, too well. We had

to pass through a sort of tunnel where the

place was simply littered with the dead. To

pass through we had at times to crawl over

them. At other times my foot splashed through

a quagmire of putrefied remains. It was dark.

To strike a match would have been fatal. I

remember that Captain Davenport who was so

ably leading his Company, struggling through

this uncovered cemetery, was with many of his

men knocked out by a shell.

I remember

the resulting chaos which followed for I was

just behind with my faithful

Liddell.

Another officer takes Davenport's place and I

tell them to carry on. For the moment I do not

know what happens to Davenport and the other

wounded. Forward, forward is the word of

command, and under the fire of a hellish

bombardment, we struggle on in and out of

shell holes, but now, thank goodness, in the

open, to our objective where I meet an enraged

British Battalion Commander from whom I have

orders to take over and who has been expecting

us for hours. I enquire for the trenches and

the position of our flanks, but he does not

know and seems to care less. Finally he

disappears and leaves me to find out where my

responsibility begins and ends.....

There were no

dugouts. The Battalion was not even sheltering

in trenches, which no longer existed, but in

shell holes.

Early morning

arrives and with it enemy shells.

Liddell and

myself (mostly Liddell) straighten things out.

We find the best shelter we can in shell

holes.

That morning, Monday, August 28th, Private

Sydney Silver, Harding's batman, wrote in his

diary:

"We are shelled to

hell. Some of the wounded look ghastly. Had

some warm shaves here today. Poor old Stokey

knocked out tonight among many others. Fed up

a bit. Hottest shop we have had together.

Things are warming up".

And, on the

following day:

"Been shelled

all night, and today with heavy thunderstorm

with shelling worse than ever. French officer

who came along says this is worse than Verdun.

Fritz dropped fifteen 5.9s in succession in

front of our hole. He had no luck. Concussion,

rotten rain and shelling makes our hole fall

in".

Liddell,

Silver and myself were together in this hole

and well do I remember it and the horrid

details of that night and day which Silver so

concisely described.

On Wednesday,

August 30th Private Silver records:

"Got out of that hole about 4 p.m.

Everyone has got out, thank God!.... C.O. badly

shaken up. Won't eat..... C.O. no better.....

Went down to Transport lines with C.O.... C.O.

no better.... Friday, September 1... C.O. saw

A.D.M.S. who sent him down to Corbie in Red

Cross car... they won't let me go any further

with C.O., who goes on tonight to the Base".

Colin Harding was

diagnosed with appendicitis and evacuated to

England for an operation....

Whilst at Stoodley Hospital in Torquay, I

heard that Ray Gough had to undergo a further

operation, I telegraphed wishing him a speedy

recovery. My wish never materialised, for the

return of post brought me a heartbroken letter

from his mother, who was with him to the last,

informing me of his death. " Death's but a

path which must be trod, if men would ever

pass to God." Ray Gough had passed that way

and God's right Hand would welcome this

gallant boy to the realms above........

Private Sidney Silver who was with me

through "thick and thin" in France, and whose

small diary, written on the spot, has helped

me to record this short account of doings in

France, eventually got promotion, was

Mentioned in Despatches and also received the

D.C.M. He saw the war through but its effects

left him in broken health and he died a year

or two ago, leaving a devoted wife and small

family to mourn his loss.

Captain

Liddell whose capabilities I have

referred to, got promotion and he eventually

became Brigade D.A.A.G. to the 17th Division,

an appointment which he filled with the

exactitude and ability which was so prominent

when helping me over nasty stiles. With the

rank of Major, Liddell retired at the

termination of hostilities taking with him a

well merited M.C. and its Bar, more than one

Mention in Despatches and the good wishes of

all his brother officers.......

n.b. D.A.A.G. stands for Deputy Assistant

Adjutant General |

Photographs of Frank Liddell's Battalion and

archived under his name are stored in the Imperial

War Museum. They were taken in 1916 in

France by a Captain Turner.

Within Frank's

papers there survives this image of him, standing

on the right at the rear, in a group of unknown

officers. It probably dates from a later period of

the war, perhaps after the appointment within 17th

Division mentioned by Colin Harding above.

In addition to "Far Bugles", quoted

from above, there is considerable information

available about the 15th Battalion and the two

other "Birmingham Pals" battalions, the 14th and

16th, in Terry Carter's book "The Birmingham Pals"

(Pen & Sword Military, 2011).

In addition to "Far Bugles", quoted

from above, there is considerable information

available about the 15th Battalion and the two

other "Birmingham Pals" battalions, the 14th and

16th, in Terry Carter's book "The Birmingham Pals"

(Pen & Sword Military, 2011).

It

appears that Frank relinquished his role of

Battalion Adjutant in April 1917 when he was

transferred to the General List (reported in the

Birmingham Daily Post on Friday 8th June 1917).

And notice of his award of the Military Cross

appeared in the London Gazette on 1st January

1918.

|

************************** |

Frank Liddell preserved a few

further fragments of his life in the Great War

which were kept in a scrapbook. They all relate to

times of leisure and give an impression of

creativity and humour at a time when the period of

death and destruction was finally drawing to a

close.

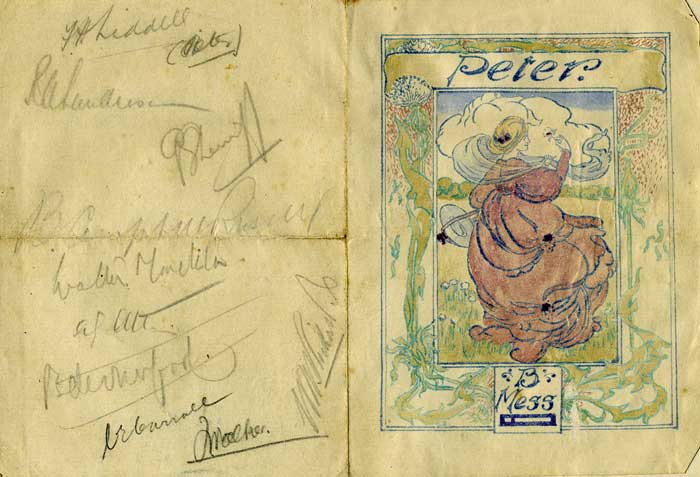

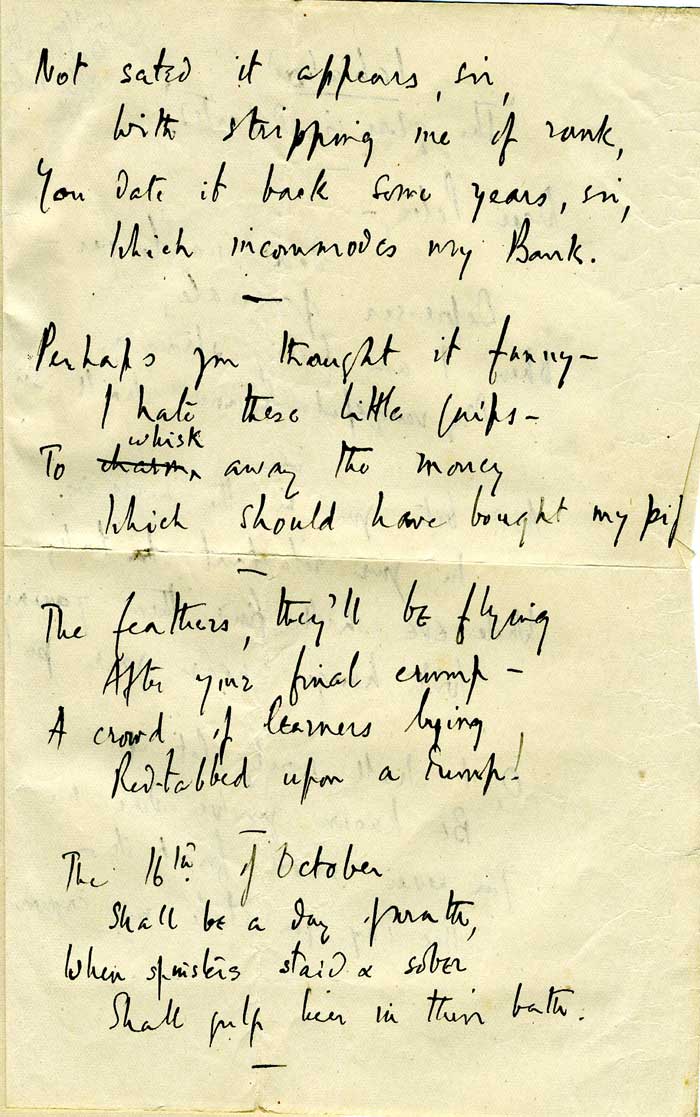

The front and rear of a leaflet,

perhaps the programme of an entertainment or a

Mess dinner, bearing the signature of Frank

Liddell (with a nickname, "Peter", an in-joke

which is now lost to us) and those of fellow

officers. Perhaps the latter were members of his

staff.

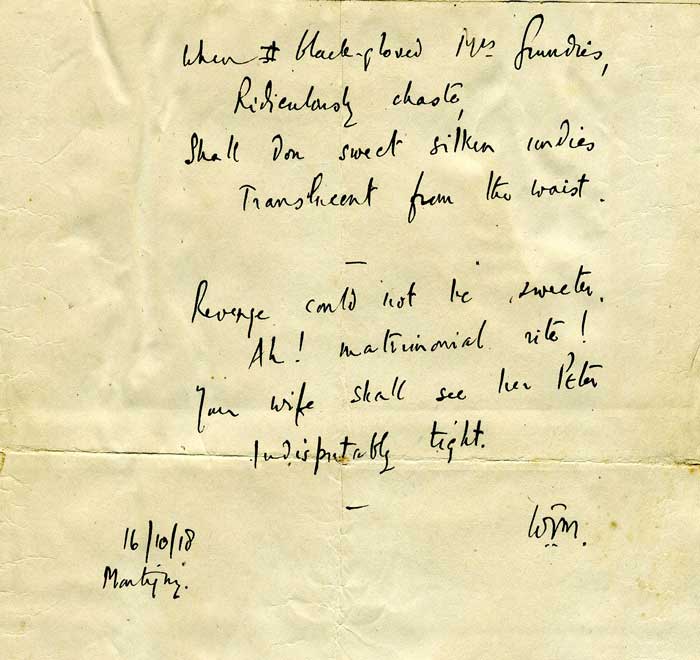

Amongst the signatures is one which

appears to be "Walter M*****", perhaps "Walter

Meredith". Is he the poet whose work Frank Liddell

felt well worth preserving for decades after the

end of the war, and until the very end of his

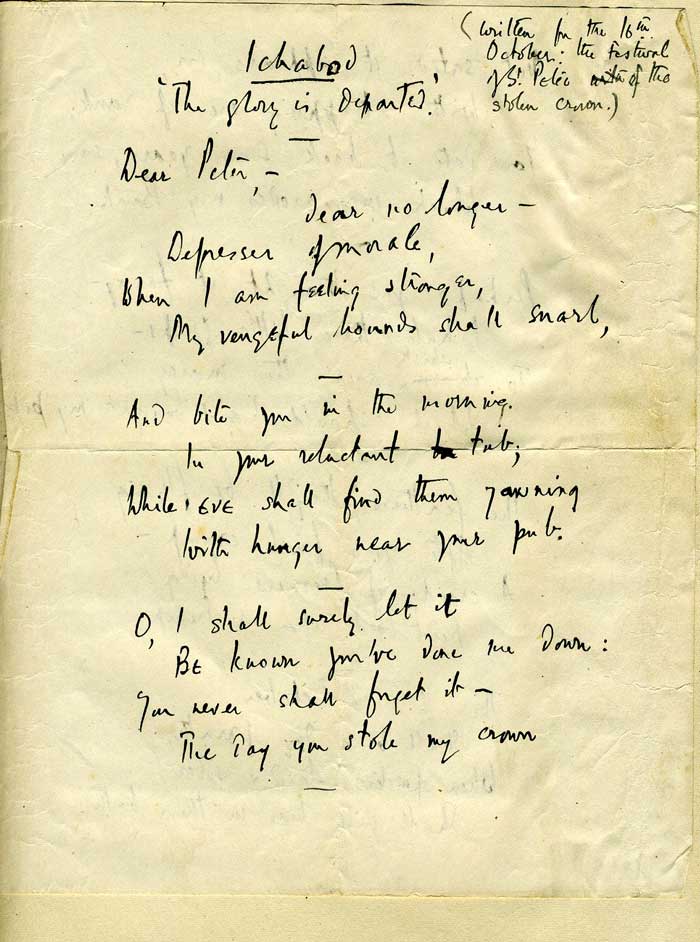

life? Here are the three examples, composed

in Martigny in October 1918, written out as fair

copies and, presumably, presented to Frank. The

Peter reference is again present.

Amongst the signatures is one which

appears to be "Walter M*****", perhaps "Walter

Meredith". Is he the poet whose work Frank Liddell

felt well worth preserving for decades after the

end of the war, and until the very end of his

life? Here are the three examples, composed

in Martigny in October 1918, written out as fair

copies and, presumably, presented to Frank. The

Peter reference is again present.

The following appears to be a (one

assumes) light-hearted reaction by someone who has

been passed over for promotion or has been

replaced. It seems to be addressed to Frank

("Peter").

The following appears to be a (one

assumes) light-hearted reaction by someone who has

been passed over for promotion or has been

replaced. It seems to be addressed to Frank

("Peter").

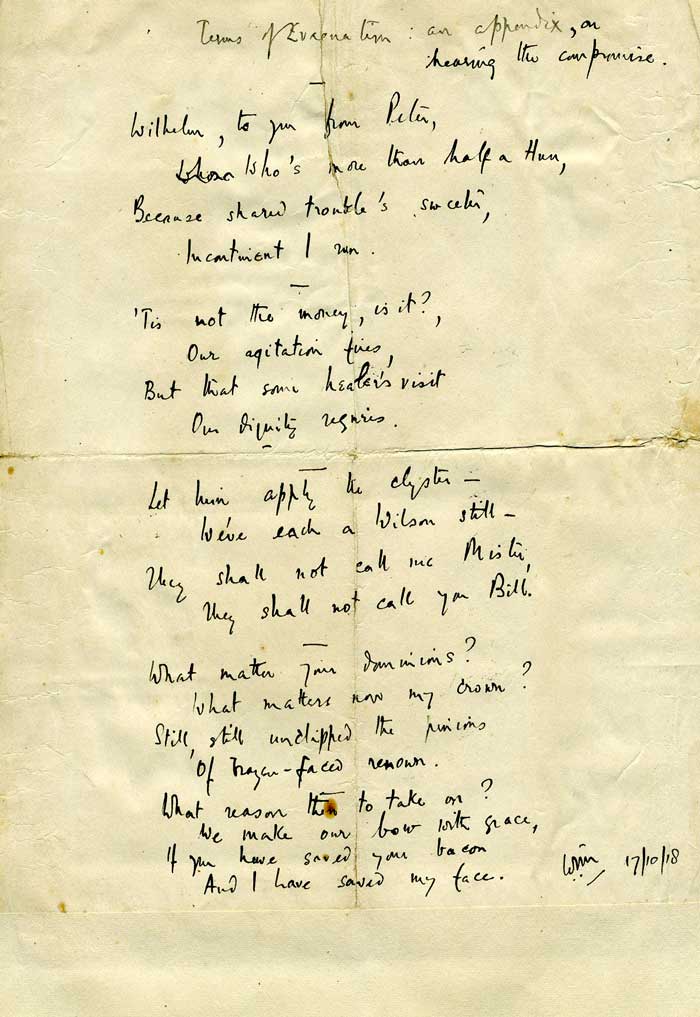

Something has changed overnight - "a

compromise".

Something has changed overnight - "a

compromise".

n.b.

"Clyster" is an

enema; the exact significance of "a Wilson" is

unknown but will be an oblique reference to the

American President. And is it Frank "who's more

than half a Hun?"

n.b.

"Clyster" is an

enema; the exact significance of "a Wilson" is

unknown but will be an oblique reference to the

American President. And is it Frank "who's more

than half a Hun?"

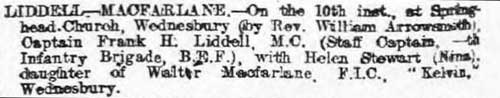

He

married before the Armistice. This is the notice

from the Daily Post of 18th

February 1918. He

married before the Armistice. This is the notice

from the Daily Post of 18th

February 1918.

Frank Liddell survived

the Great War as so many of his brother officers

and men did not. He spent the rest of his life in

Shrewsbury where he owned the Della Porta department

store in High Street. In that town he was a leading member of the

community for decades - before, during and after

the Second World War - and for four years commanded

the 1st Shropshire Battalion

of the Home Guard.

In Memory of

Lt.-Col. Frank H.

Liddell

and

all his comrades in the

1st Shropshire Battalion |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Staffshomeguard is

most grateful to Mandy Peat, Col. Liddell's

grand-daughter, for generously passing on

images and information about her grandfather

and permitting their publication in this

website; and to Terry Carter for information

from the London Gazette and contemporary

newspapers.

FURTHER

INFORMATION

Further information about the

Home Guard in Shrewsbury is contained

elsewhere in various parts of this website. To view the

Shropshire summary page, please use the

Shropshire Page link below.

And if you

can add anything to the history of the

Shropshire Home

Guard, please contact staffshomeguard via the

Feedback link.

|

|

x119B June 2015 |

|