This

wonderful memoir was recorded on tape by William Leslie

Frost (1913-1984) shortly before he died. He is pictured

left in the early 1940s when he was working at Joseph Sankey

& Co. Ltd. as a draughtsman. The memoir

describes his service in a Shropshire Home Guard unit between

1940 and 1944 which he undertook in addition to his responsibilities

as a designer working on Spitfire fuselage construction.

It was transcribed and edited by his son, Allan J. Frost,

and was first published in the Wellington News in November

2005.

This

wonderful memoir was recorded on tape by William Leslie

Frost (1913-1984) shortly before he died. He is pictured

left in the early 1940s when he was working at Joseph Sankey

& Co. Ltd. as a draughtsman. The memoir

describes his service in a Shropshire Home Guard unit between

1940 and 1944 which he undertook in addition to his responsibilities

as a designer working on Spitfire fuselage construction.

It was transcribed and edited by his son, Allan J. Frost,

and was first published in the Wellington News in November

2005.

(We

are deeply indebted to Allan Frost for allowing us to reproduce

this memoir and its accompanying illustrations on this website.

Mr. Frost is a well known historian specialising in the

history of Wellington, Shropshire, and has a number of fascinating

books to his credit. Please click

here for information on these and full contact details

for the author.)

LESLIE

FROST AND THE WAR YEARS

During the war I was in

what you'd call a reserved occupation at

Sankey's in

Hadley.

They didn't look kindly to anybody disappearing at that

time if they'd got any experience, particularly in the engineering

world. They didn't take kindly to people volunteering and

clearing off and, as it happened, I got stuck on Spitfire

fuselage assemblies, I was responsible for the drawing office

ends of things if the drawings came from Vickers headquarters

at Castle Bromwich, the Spitfire headquarters: management

at Sankeys sent the drawings through to me for amendment.

It was my job and responsibility to see that Vickers got

the latest drawings. If any alterations or repairs were

wanted to be effected during the assembly of these things,

then I used to have to make the drawings out for them and

apply for the concession to be made so they could be passed

by their engineers and then passed through to the Air Ministry

inspection department for them to follow up as well, so

everybody had records of them. It was amazing the number

of times that repairs were needed! And sometimes, of course,

there was a problem when air operations were in progress

(something giving way or wanted strengthening) and emergency

operations had to be put in to strengthen where necessary:

these came through to me again to see that whatever necessary

was carried through.

And that was more or less

what I was on all the time during the war. Which meant considerable

alteration down at Sankey's itself because access to the

works was only down one narrow lane and over two railways

so that personnel had to walk down under two bridges but

materials and stuff had to come to come to the firm over

the top of the railways and over level crossings. Then down

to the front of the factory, which had only got a comparatively

narrow entrance. The material for the fuselages and the

framework, etc., had to be transported halfway across the

works to the far end of the factory. So that's how the main

entrance later came into being from the

Leegomery end. A

new road was put through to it and it certainly made it

far easier to facilitate the in and out of materials and

made a big difference to the firm itself as it started expanding:

production was wanted and production was needed. In addition

to the Spitfires there were the spinner cones for Wellington

bombers. We did one or two wings for Wellingtons as well,

but the Spitfire was the main concern and at one stage we

were getting around 3 or 4 fuselages a day out, complete

with engine, and shipping them off to Castle Bromwich.

Well, when the invasion

scare came in 1940, well before it actually happened, the

government decided to form Local Defence Volunteers to help

to patrol and watch for any of the parachutists being dropped

over here, as spies I suppose: you never knew whether you

were being told truth or lies during the war. The first

casualty of war is truth. We had no weapons; it was after

Dunkirk when the big evacuation came through and the blitz

had started. There wasn't enough weaponry to go round the

existing forces let alone anybody else, so people were wandering

round the countryside looking and ducking and vanishing.

That's what LDV stood for, 'Look, Duck and Vanish': you

were told to do that because you'd got nothing to do anything

else with!

The idea was to report anything

unusual and we went wandering round the countryside on bikes:

one big advantage was that you could go anywhere on anybody's

land and you couldn't be stopped. There was no question

of anybody trespassing or anything like that. You had the

right to go wherever you fancied. Certain areas were mapped

out as routes, so you patrolled these areas and used these

routes but there's more than one (not in my case, I might

say!) person's cabbages and beans had disappeared out of

the various gardens up and down the country which were not

the result of enemy action. But taking it by and large,

the system worked reasonably well until munitions supplies

started to come from Canada and America. When the position

improved, the Government decided to run us on a more military

basis and formed the Home Guard in proper army units. We

were affiliated to the Regular army units of the KSLI (King's

Shropshire Light Infantry) and we were in the 5th Battalion.

We belonged to "D" Company whose headquarters

were up at Wrekin College. One of the masters at the Wrekin

College with the same surname as myself, Frost,

was the company commander but my platoon was based at Blockley's

Brick Works at Hadley, under my old boss Mr.

Shaw.

Mr. Shaw was an old 1914-18

War veteran who'd been to Gallipoli and places like that.

So that's how we formed up and started training. Regular

soldiers came down to shove us through our paces, which

was a very peculiar thing because we had such a mixed bag

of odds in this Hadley platoon. There were people from Leegomery,

farm labourers, older ones of course, who were a bit short-winded.

There were us younger ones who were pretty fit and there

were all shapes and sizes in between. So, when you were

put through your paces, the younger ones were luckier because

they could stand the pace while the older ones couldn't.

And we had to do quite a bit of reading before the people

who came in to instruct us realised the state they were

in.

I seem to have had an eye

for shooting because it wasn't very often I didn't get a

possible top score with a gun on the 200 yard range they

built up at Blockley's clay pits: they dug a trench out

at the back, like at the Wrekin firing range, where the

people manipulated targets and indicated whether the shots

were on target. The targets were under/over ones. I seem

to have kept at it except when I started to wear glasses

and, of course, you cannot focus properly at all with glasses.

I joined just as an ordinary

private but I thought to myself, 'Well, if it ever becomes

necessary and you really are wanted, the more efficient

you are the better.' So I used to get stuck into the exercises

and swatted. You could buy books on things and borrow official

books on grenades.

Eventually, after a year or so, I went to a couple of courses,

one down south and another up near Southport to train as

a weapons training officer. Most of that was to do with

grenades, so at the finish I was quite proficient on those.

We had to do the practical ends of things as well, such

as what you had to do when the bombs didn't go off and had

to destroy them. I became more and more interested in that

side ofthings to be quite honest. I made myself

grenades.

Eventually, after a year or so, I went to a couple of courses,

one down south and another up near Southport to train as

a weapons training officer. Most of that was to do with

grenades, so at the finish I was quite proficient on those.

We had to do the practical ends of things as well, such

as what you had to do when the bombs didn't go off and had

to destroy them. I became more and more interested in that

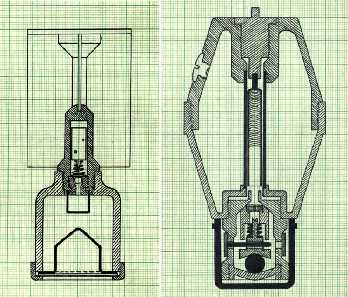

side ofthings to be quite honest. I made myself some models and thingslike that to demonstrate how these

things worked and, of course, you can't do things like that

without coming to the notice of others. So eventually I

was made a Lance Corporal and then a Corps Sergeant and

ended up as a Second Lieutenant and Training Officer for

the Company. With powers to do all the necessary training,

organise the training, review any new weapons coming through,

all this had to be done by me for the company. And we had

a subsistence allowance of 1/6d

(7.5p) when we went on patrol

and had to stop out most of the night, to provide our refreshments

if we could get them off our rations. We did have a bit

of concession, I suppose, in that we had a bit of tea, free

tea and things like that. That's how it worked out.

some models and thingslike that to demonstrate how these

things worked and, of course, you can't do things like that

without coming to the notice of others. So eventually I

was made a Lance Corporal and then a Corps Sergeant and

ended up as a Second Lieutenant and Training Officer for

the Company. With powers to do all the necessary training,

organise the training, review any new weapons coming through,

all this had to be done by me for the company. And we had

a subsistence allowance of 1/6d

(7.5p) when we went on patrol

and had to stop out most of the night, to provide our refreshments

if we could get them off our rations. We did have a bit

of concession, I suppose, in that we had a bit of tea, free

tea and things like that. That's how it worked out.

We used to stay the night

up at Blockley's works, which was all right during the summer

but when winter came we didn't go out on patrol but had

to stop there to man the communications centre. On one occasion,

when we came to use the teapot, it was full of, er, well,

we'd forgot to empty out the dregs from a month or two before

and there was a lot of penicillin in it which had to be

scalded out! One of the drawbacks was that I lived near

the drill hall in Wellington, so whenever our company was

supposed to be on duty there and didn't turn up (which happened

quite often), I was dug out late at night or in the early

hours to go and stop at the drill hall in the communications

room, at the top of a bunk (with rats scurrying around underneath)

in case phone calls come through. I never had a phone call

but whether they'd come through or not when I was asleep

I don't know!

The arsenal, the

Woolwich

Arsenal, moved up to Donnington. When the workers came up

there were no houses for them and, although we'd got a baby

and my wife's old Mum (we'd plenty to do to look after them)

as we'd got a spare bedroom, we should have one of these

London chappies billeted on us. And he proved to be a very

nice fellow all round, a decent chap, and he did provide

access to black market eggs and things like that from the

local pub where he went to have his drink.

We looked after an evacuee

from Smethwick for a short while; she left when her parents

had to contribute a little to her keep. She was a twelve

year old.

My daughter had been born

in August 1939, just before the War started. My elderly

mother-in-law died in 1942. One of her grandsons came over

with the American Forces (that branch of her family had

emigrated to America thirty-odd years earlier) a few months

later to see her but he could only visit her grave in Wellington

cemetery. My first son was born in 1943. Near the time he

was due to be born, I was encouraged to go on a course down

at Dorking, a Home Guard course on grenades and weapon training,

with a view to becoming a weapon training bloke myself.

I had become very interested in these things and, with typical

military efficiency, I was sent down a day too early, travelling

down with my rifle and equipment and my allocation of the

one or two rounds of ammunition they dare let us have. Because

I was a day early, they didn't know anything about me. I

said, 'Well, you'd better find out something about me because

I want to come and I don't want to stop on the station all

night.' So they sent a little truck to fetch me: it turned

out to be the Lord Lieutenant of the County's place where

this course was being run. Rank went by the board, everybody

was in the big dining hall with the portraits of the Lord

Lieutenant of the County's ancestors round the walls, with

tablecloths, proper cutlery… and tipping everywhere you

went!

It was a very interesting

course, actually. I always remember one moment when it didn't

seem to be such a good idea when the chappie who was taking

us on mines was talking to us and had a mine in front of

him. He was pretty deaf because of the bangs and explosions

he'd  been

through during his operations and training and he kept idly

pressing up and down on top of the mine; fortunately it

was a dummy one but everywhere we went (to a grenade range,

to the firing range, to the bombardier range, the spigot

mortars range, etc.) there was a tip for the driver, another

tip for the driver and so on. I always remember the first

night being there: I ended up in the

stoke hole with a little Irish

been

through during his operations and training and he kept idly

pressing up and down on top of the mine; fortunately it

was a dummy one but everywhere we went (to a grenade range,

to the firing range, to the bombardier range, the spigot

mortars range, etc.) there was a tip for the driver, another

tip for the driver and so on. I always remember the first

night being there: I ended up in the

stoke hole with a little Irish  bod who was three parts slewed

with a bottle of whisky by the side of him. We were sitting

there looking at the stoke hole and what he wouldn't have

done to the Pope if he'd have had him there! He'd have stuffed

him up the stoke hole and all sorts of things! To me it

seemed funny at the time. In view of what happens nowadays

you realise how far back these things go because he wasn't

joking.

bod who was three parts slewed

with a bottle of whisky by the side of him. We were sitting

there looking at the stoke hole and what he wouldn't have

done to the Pope if he'd have had him there! He'd have stuffed

him up the stoke hole and all sorts of things! To me it

seemed funny at the time. In view of what happens nowadays

you realise how far back these things go because he wasn't

joking.

It was a very interesting

time down there. I was most impressed with the full gas

hedge-hopper, which consisted of a forty gallon mixture

of tar and oil and all sorts of things like that with a

charge underneath it; the ideal thing was you waited until

an enemy tank was just the other side of a hedge, and you

blew it up. The idea was that you just tried to hawk it

over the hedge, set it on fire so it smothered the tank

and enveloped it in flame. Unfortunately, (or fortunately

as it went a bit wrong) one had a bit too much charge underneath

it (it was a delicate operation) and it went up in the air

in one big ball of fire about 50 feet across, very impressive!

Another incident on the

range was when we went to throw the anti-tank mines and

lob them over the hedge into the tracks of the tanks. The

mines were in the shape of a Thermos flask. The aim was

to get them close to the tank, not from over a hedge like

we did in practice, because that isn't any protection against

small arms fire or any other fire, but from behind a suitable

wall from where you could lob it. You took the cap off the

mine, a little tape was wound round the handle and round

the fuse, with a lead weight on the end… and you lobbed

it over. However, when I got to the officer after the throwing

part of the proceedings, he looked a bit shaken when he

asked my companion, a little Welshman. 'How did you get

on? 'Oh', says the Welshman. 'Oh, I chucked mine up. The

tape came out and all the rest, but it dropped down at our

feet… and it didn't go off.' 'It didn't go off?! You two

are the luckiest people alive!'

I enjoyed the holiday down

there, and the luxury. A change during the war years. When

I returned home, I was fully expecting to find whatever

it was, a boy or a girl, would have arrived. But he hadn't.

My son was born a week later than expected. I wouldn't have

known if the anti-tank mine had done its job properly!

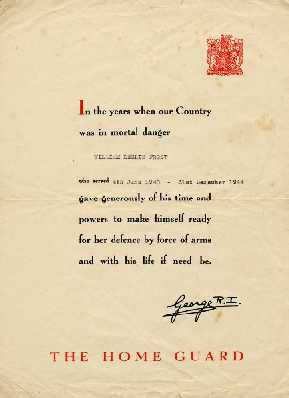

Postscript

Leslie Frost died in December

1984. A working plywood model of a hand grenade (used in

his Home Guard training sessions) and countless grenade

firing pins were discovered in the attic of his home in

King Street, Wellington, together with his sub-lieutenant's

swagger stick. The attic also contained several rounds of

live rifle ammunition, two hand grenades (defused) and a

smoke bomb (still primed for use). And, of course, his Certificate

of Commendation from H.M. King George VIth.

Allan Frost

1st

January 2006

© Allan J. Frost

2006