A

MEMORY OF NEW STREET

Winter 1942/43

|

There is already a small queue at the

bus shelter in New Street. My mother and I join the end

of it. People hurry by us in both directions, their clothing

mainly dark and devoid of colour, their faces pale. The

majority are women, carrying shopping bags or tugging

children; almost all wear a felt hat of some sort with

just the odd one bare-headed or in a head-scarf tied in

the form of a turban. Hats, overcoats, gloves, scarves,

nothing of what they wear is fresh or new. Just down the

street a newspaper seller is offering the two local evening

papers, the Despatch and the Mail, with the familiar cry: "Spatchermile.........

spatchermile". Above all of our heads in the cold,

winter sky the first few starlings are returning to their

homes on roofs and ledges after a day of foraging in parks

and suburban gardens. Soon there will be thousands of

them, wheeling overhead in great dark clouds, their chirping

a continuous chorus almost drowning out the noise of the

traffic. How strange is their desire to rush into the

city centre at this time of the day when I and everyone

else are happy to be leaving it.

Earlier we have been in

Lewis's, a regular

destination for our visits to Birmingham in my school

holidays. Afterwards I walk down

Corporation Street holding

my mother's hand. We make a quick visit into

Midland Educational

for some minor item connected with my schooling. As usual

the contents of the shop do not register much with me

- after all, it is not a proper toyshop - and in any case

I possess in my mind no standard by which to measure the

inadequacy of the wartime stock. Then it is into

Pattison's

where my mother is due to meet an old office friend of

hers, Mrs. Hewitt, an

older lady with whom she had worked

at the Law Courts at the other end of Corporation Street

in 1918 when an earlier war had been raging. There they

had both typed for an up-and-coming young Birmingham barrister,

Norman Birkett, later

Baron Birkett of Ulverston, of whom great things had been expected

which would later be achieved in full as he eventually

attained high office in the Judiciary.

older lady with whom she had worked

at the Law Courts at the other end of Corporation Street

in 1918 when an earlier war had been raging. There they

had both typed for an up-and-coming young Birmingham barrister,

Norman Birkett, later

Baron Birkett of Ulverston, of whom great things had been expected

which would later be achieved in full as he eventually

attained high office in the Judiciary.

(Here is my mother at

around that time -

second from right - on the roof of the Law Courts

with three of her colleagues).

The three of us

are seated at a small round table in the cafe, the ladies

nattering. I sit transfixed with boredom, trying not to

look at a brimming ashtray in the middle of the table,

its pile of butt ends still showing traces of the lipstick

or saliva of total strangers and being added to every

ten minutes or so by my mother and her friend. It is an

image and a feeling of disgust which I shall retain all

my life and will ensure that whatever I die of, it will

not be smoking-related. I munch my slice of sponge cake,

a dry affair with a smear of red, fruitless jam inside

it - the finding of any trace of a genuine strawberry

on such occasions would be a miracle - and sip my cup

of tea. The cup is cracked, like many others. My mother

notices it. "Drink from near the handle, dear, and

avoid the crack", she whispers to me. It's a familiar

refrain.

After saying our goodbyes, accompanied

on my part by the obligatory raising of school cap, we

walk on down Corporation Street. Beyond the junction with

New Street and further in the distance we can see the

smoke-blackened, Victorian edifice of

New Street Station, its entrance

as usual bustling with activity. Where the two streets

intersect we cross diagonally in two stages using the

central reservation. This pedestrian refuge prevents the

two opposing streams of one-way New Street traffic from

colliding and feeds them from each direction either into

Stephenson Place towards the station or up along Corporation

Street. We turn left and slowly walk the few yards down

New Street in the general direction of the

Bull Ring to

reach our bus shelter and join our fellow passengers,

all of us waiting for the No. 113 Midland Red. There is

no need to hurry.

Eventually - but not for at least another

quarter of an hour - our bus, always a double-decker,

will appear and I can anticipate that moment. It

will emerge from High Street to our right

in front of a tall, modern building bearing the name

"The

Times Furnishing Co"; its white façade appears

undamaged in contrast to the wrecked buildings beside

it. (I can never understand why a Birmingham shop should

bear the name of a newspaper - it is just one of life's

many mysteries). Then it will pull up in front of us having

reached its terminus and stand there, rattling in time

with the throb of its engine and emitting a smell of scorched

brake or clutch lining.

At this stage of the day few people will alight, perhaps a

soldier or airman or sailor stepping confidently off the

back of the platform in the direction of travel before the

bus comes to a stop and then hoisting kit bag onto

shoulder and striding purposefully off in the direction of

New Street Station or

Snow Hill.

When

all its homeward bound passengers have boarded, I know

that the bus

will set off, moving diagonally to the right across

New

Street, as it always does,

before rounding the corner and roaring off up

Corporation Street past the shops we have recently

visited, then turning left into

Bull Street and pulling

up outside Grey's department store. Here another group

of home-going passengers will step off the pavement and

clamber aboard. Then off again, turning right in front

of Snow Hill Station into

Steelhouse Lane and, once past

the General Hospital, left into

Loveday Street. We shall

now have moved away from the central area of the city

but the buildings will still be tall, towering over the

bus. Every so often there are gaps where the Luftwaffe

has done its work. These bomb sites will sometimes have

been cleared but more often still contain a great pile

of rubble covered by dull, winter vegetation and the

remains of last autumn's willow herb. Usually they are

bounded by a sheer, blank wall, that of an adjoining

building which has somehow survived, and sometimes shorn

up by vast timbers. Such walls fascinate me. They are

often studded throughout their height by rows of little

fireplaces, the colour of the tiles still bright and a

small rectangle of the surrounding wall bearing the

flowered wallpaper of a living room or bedroom. I find

difficulty in reconciling these sights with my own

experience. Fireplaces should be on the ground floor, in

a lounge or dining room, or perhaps one storey up, in a

bedroom. But not stretching up three or four floors,

almost up to the sky. And who used to sit around them

and where are they now?

As the bus passes through

Aston along

Summer Lane I know that the buildings will become smaller, side-street

after side-street of back-to-back terraced houses, sometimes

with a gaping hole in their midst or a row of homes damaged

and boarded up. Past the Crocodile Works where, despite what my elder sister tells me with a straight face on another occasion, I am well aware that they make something other than large predatory reptiles. Then onward through

Perry Barr with its cinema

and shops and the junction where the Outer Circle buses

cross our path; and onward towards

New Oscott and

College

Arms where our route turns left on to the

Chester Road.

After Beggar's Bush there is the feeling that we have

finally left the city behind as

Sutton Park spreads out

to our right. Onward past Banner's Gate and the

Parson

& Clerk. There is much evidence of 1930s building

along the road here in Streetly, abruptly brought to a

halt in 1939; I shall later learn that this is called

"ribbon development". But it is by no means

continuous and from the top of the bus I shall be able

to look out, here and there, over great swathes of open

countryside. At each stop we disgorge another small group

of passengers. The last of them leaves at the

Hardwick

Arms crossroads where the bus will turn and park on the

main road near to Cutler's Garage,

ready for its return to the city. But that is all to come.......

We are still here, in the bustle

of New Street. I anticipate the journey, undertaken

so many times before. But it is not

our turn yet. My mother and I stand there, waiting for

the 4.15 to arrive, and look out across the street. It is a

year or two after the bombing of 1940 and 1941. As far

as I am concerned the street has always looked like this

and probably always will. The buildings behind me seem

to have emerged unscathed. The Odeon cinema, a few paces

down the street, appears to be open, as is a crowded little

snack bar near to where we are standing. Of course it

is difficult to tell what the state of the upper storeys

is and, anyway, that is all part of normal life and not

really of any interest to me at all.

On the other side of the street, though,

it is a different story. Directly opposite is

Horne's,

a gentlemen's outfitters housed in an ornate Victorian

brick building similar to many further up

New Street towards

the Town Hall. It is open for business. But I think that

it is only part of the ground floor which is available

to the owners. Above, the windows seem to be missing or

blanked out; behind them one assumes is chaos, scorched

debris, fallen timbers, missing roof. I can see some lights

on already somewhere within, in the area which is open

to customers. The official blackout time is still an hour

or two away after which not the faintest glimmer will

be visible; but I shall be safely back home by then.

To the left of Horne's is a building which

always fascinates me. It is, or rather was, a tall, light-coloured,

confident modern building, but it is now grubby and forlorn.

My mother tells me that it used to be

Marshall and Snelgrove's,

a beautiful shop which she visited from time to time and

I try to imagine it in its original state, its white façade

pristine and crowds of customers going in and out of its

doors.

I must have seen it then but was too young for

the image to have registered. Today it is just a shell,

still standing, but above each of its many curved windows,

now blank and gaping, a great black smear stretches up

the stonework where flames and smoke erupted from within

as the interior was being consumed. This image

(left)

shows a fire being dealt with, next door, during the

morning of 25th September 1940. Perhaps the shop was

damaged at that time; but it was a month later, in

October, when the building was wholly burnt out, to create

the appearance which I am now seeing. It is hard to

imagine

how it can ever be restored to its former glory but it

will be, eventually, in the form of a replacement with

a broader façade and in a rough approximation of

the original form and texture.

I must have seen it then but was too young for

the image to have registered. Today it is just a shell,

still standing, but above each of its many curved windows,

now blank and gaping, a great black smear stretches up

the stonework where flames and smoke erupted from within

as the interior was being consumed. This image

(left)

shows a fire being dealt with, next door, during the

morning of 25th September 1940. Perhaps the shop was

damaged at that time; but it was a month later, in

October, when the building was wholly burnt out, to create

the appearance which I am now seeing. It is hard to

imagine

how it can ever be restored to its former glory but it

will be, eventually, in the form of a replacement with

a broader façade and in a rough approximation of

the original form and texture.

The traffic between me and these buildings

is light. It is passing from right to left. Much of it is buses, the red

Midland and the

dark-blue and yellow Birmingham Corporation on which I

very rarely travel. Almost all are double-deckers, seating

over 50 people and carrying many more standing but only

on the lower deck. It is mainly the Midland Red that I

notice, the ones I am most familiar with. Most originate

from pre-war; they are solid, substantial vehicles retaining

their padded, cloth upholstery, with registration prefixes

of HA or AHA. But increasingly they are being supplemented

by the newer "utility" buses, gaunt, angular,

spindly vehicles with hard suspension and slatted wooden

seats. From time to time a single-decker will pass, of

pre-war vintage and occasionally very antique, even to

my eyes, dating back to the very early 1930s. There are

a few cars, almost all of them black in colour, and often

a railway mechanical horse, a strange, articulated vehicle

consisting of a flat platform or a boxed-in van structure,

hauled by a three-wheeled "horse".

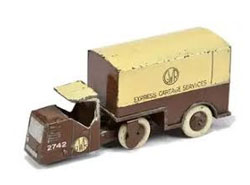

(My favourite

Dinky Toy is a pre-war representation of one of these

vehicles

(right) in the chocolate and cream livery of the

Great

Western Railway Company; one day in the future it will

disappear, perhaps liberated by a playmate who finds it

attractions irresistible). Occasionally a car will pass

with a huge, wallowing rubber bag lashed to its roof,

overhanging both bonnet and boot and filled with town

gas to fuel its progress in these days of tight petrol

rationing. All of these vehicles will have fitted over

their headlamps the familiar, round, black, metal masks

bearing rows of hooded, horizontal slits through which

glimmers of light will emerge to help the vehicle feel its

way after dark. The edges of mudwings and other extremities

on all the public vehicles and many of the private ones

are painted white to give pedestrians and other road users

a chance of seeing the vehicle looming out of the darkness.

(My favourite

Dinky Toy is a pre-war representation of one of these

vehicles

(right) in the chocolate and cream livery of the

Great

Western Railway Company; one day in the future it will

disappear, perhaps liberated by a playmate who finds it

attractions irresistible). Occasionally a car will pass

with a huge, wallowing rubber bag lashed to its roof,

overhanging both bonnet and boot and filled with town

gas to fuel its progress in these days of tight petrol

rationing. All of these vehicles will have fitted over

their headlamps the familiar, round, black, metal masks

bearing rows of hooded, horizontal slits through which

glimmers of light will emerge to help the vehicle feel its

way after dark. The edges of mudwings and other extremities

on all the public vehicles and many of the private ones

are painted white to give pedestrians and other road users

a chance of seeing the vehicle looming out of the darkness.

There are still horse-drawn vehicles about,

usually brewers' drays bearing the name of their owners,

Ansells or

Mitchell & Butlers, or carts belonging

to the LMS or

GWR. One of these vehicles draws up alongside

the pavement to my right, as they sometimes do. The driver

in muffler and cloth cap gets down off his cart, comes

to the head of the horse and ties on its nosebag. As he

completes this operation the horse starts to eat and simultaneously

decides to empty its bladder, to my delight. What amazes

me is the volume that the animal produces. It spreads

out for several feet around over the surface of the street,

and lingers there on the cobbles, steaming in the cold

air. The driver pays not the slightest attention and moves

down the flank to adjust the harness in some way. In fascination

I watch his small, hob-nailed boots splash through the

pool with a muffled clatter. He doesn't even glance down.

And here's me, I ponder, who gets ticked off for even

thinking of walking through a puddle of rainwater.

There are still horse-drawn vehicles about,

usually brewers' drays bearing the name of their owners,

Ansells or

Mitchell & Butlers, or carts belonging

to the LMS or

GWR. One of these vehicles draws up alongside

the pavement to my right, as they sometimes do. The driver

in muffler and cloth cap gets down off his cart, comes

to the head of the horse and ties on its nosebag. As he

completes this operation the horse starts to eat and simultaneously

decides to empty its bladder, to my delight. What amazes

me is the volume that the animal produces. It spreads

out for several feet around over the surface of the street,

and lingers there on the cobbles, steaming in the cold

air. The driver pays not the slightest attention and moves

down the flank to adjust the harness in some way. In fascination

I watch his small, hob-nailed boots splash through the

pool with a muffled clatter. He doesn't even glance down.

And here's me, I ponder, who gets ticked off for even

thinking of walking through a puddle of rainwater.

Buses arrive although still not yet ours.

The bus-stops along this part of

New Street serve mainly

the routes out of Birmingham to the north of the city,

all Midland Red.

The 118 goes to Walsall and there is a series of numbers

denoting routes via the middle of

Sutton Coldfield. The

101 goes to Streetly, as ours does, but travels via Sutton

and terminates in Streetly village; the 102 to

Mere Green,

the 103 to Canwell. The 104, a more infrequent service,

is always operated by a single-decker and pursues a circuitous

route from New Street through Sutton and Streetly before

disappearing off down the Chester Road towards

Brownhills

and finally ending up somewhere over the horizon in a

distant place called Cannock. Another service which picks

up here in New Street is one which is always identified

by the conductor bellowing "Beeches" as he is

doing today, meaning, as I find out much later, the

Perry

Beeches Estate at Great Barr.

As our queue lengthens a flower seller

approaches us. She is offering small bunches of lavender.

She has a dreadful deformity in one of her arms which

appals me and I try not to look at it. She is either ignored

or dismissed with a slight shake of the head by our fellow

passengers. She accepts these rejections resignedly and

approaches us. My mother

(right, in 1906/7) is a gentle soul who once told

me about a lavender seller of her Edwardian childhood

who had a pitch in

Station Street, the sight being so

pathetic that it used to make her cry and beg her grandmother

to hand over a few coppers. In character, she uses a few kindly and gentle words

as she declines the offer. She is

rewarded by a torrent of abuse before the seller moves

on to the next group of potential customers.

As our queue lengthens a flower seller

approaches us. She is offering small bunches of lavender.

She has a dreadful deformity in one of her arms which

appals me and I try not to look at it. She is either ignored

or dismissed with a slight shake of the head by our fellow

passengers. She accepts these rejections resignedly and

approaches us. My mother

(right, in 1906/7) is a gentle soul who once told

me about a lavender seller of her Edwardian childhood

who had a pitch in

Station Street, the sight being so

pathetic that it used to make her cry and beg her grandmother

to hand over a few coppers. In character, she uses a few kindly and gentle words

as she declines the offer. She is

rewarded by a torrent of abuse before the seller moves

on to the next group of potential customers.

As my mother recovers from the hurt my

eye moves back to the other side of the street. To the

right of Horne's there is nothing. A vast expanse of flat

ground, not a trace of the Victorian and Edwardian buildings

which once towered there. Nothing. The rubble which spilled

out over New Street the morning after the bombing has

all gone and with it every vestige of this part of the

earlier Birmingham. One can see right across to

High Street

where the row of buses probably includes our own. The

flat area acquires the name of

Big Top when a vast marquee

is erected on it for the purpose of circus or other entertainment.

I shall be there in a few weeks, as a birthday treat,

to see the circus. We will go on a day of strong wind

and be surrounded by the noise of slapping canvas and

creaking structure as we laugh at the clowns and watch

the parading horses. It will be a relief to my mother

to emerge unscathed. A day or so later, after a further

increase in the strength of the winds, we will read in

the Evening Mail that the tent has blown down.

But that is in the future and back here

in the present our bus has arrived. We shuffle on board

and at my insistence climb the stairs to the top deck

which is less crowded and where the view is far better.

The fug of cigarette smoke starts to grow as more passengers

light up but that is just about tolerable, as is the thought

which always lurks in the back of the mind: whether the

driver of this unwieldy and top-heavy vehicle will exercise

due caution when negotiating the tighter bends on the

journey. The conductor squeezes down the central aisle

in order to collect our fares, holding a clipboard containing

a row of different coloured paper tickets, starting with

a white one for a fare of one penny. My mother offers

the correct fare and two tickets are extracted, punched

in a little machine which dangles around the conductor's

neck and handed over. Then she - for more often than not

these days the conductors are, more accurately, conductresses

- moves on down the aisle to the next passenger.

I sit there and gaze out of the window

at a Birmingham whole areas of which will disappear within

a couple of decades, a concept quite beyond my wildest

dreams or comprehension. My thoughts are shorter term,

just as far ahead as this coming evening. Tonight is

ITMA

and Tommy Handley on the wireless. I shall listen and laugh, and later

will probably lie on the soft hearth rug in front of the

open fire while the faithful wireless continues to mutter

in the background, bringing the latest news from

Russia

or North Africa or the

Far East,

or of last night's bombing raid on the

Ruhr. I shall stretch

out there on my front, chin resting on my hands, and gaze

deep into the glowing coals. There I shall see frightening

caverns and passageways opening up, with flames of red

and orange and purple within, spitting and sizzling, flaring

and fading; for me they will be images of a burning city.

And then I shall try to imagine what peace will be like,

if it ever comes. But that is an unnatural state and one

I never succeed in visualising, this or any other evening.......

**********

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND OTHER

COMMENT

All of the

above recollections are as honest and accurate as the

author can make them, subject to distortions of the

memory over many decades. But any correction, and in

particular comment on any anachronism which might have crept in, will be welcomed.

Please use the website

Feedback

function on the Home Page; or post in the thread in the

Local History group/Forum if that has been your route to

this page.

Grateful

acknowledgement is made to the unknown original owners

of the several street scenes above and of the Dinky Toy

image.

All other images

are from the Myers Family Archive.

Unless otherwise

stated all images and text are

© staffshomeguard

2007-2024